a requiem for "The Future"

What is the object of the verb "to future"? What is its subject? And what are the implications of the answers to those two questions?

This essay is concerned with brief answers to two questions, of which this is the first: what is it that we work on, when we do futuring? What is the object of the verb "to future", what is it that is operated upon?

The most obvious answer to this first question is very false. One does not—one cannot—work on or with "The Future", because it does not exist; there is no such thing.

To use the definite article with a noun so inherently unbounded and indefinite is the foundational error of the field, and while it is thankfully approaching the status of cliche to hear someone correct the term by pointedly pluralising it, the habit of thinking "The Future" persists.

In many respects, this is understandable. After all, "The Future" has been regularly invoked as a sociopolitical and economic character in a whole range of narratives for many years. More to the point, the history of the notion of a monolithic, definite and predictable future is to some extent coextensive with the history of modernity and capitalism, and arguably with rationalism and post-Enlightenment thought more broadly.

(Or, to put it another way: "The Future" is the increasingly amok and rickety art project that we built in our philosophical backyard, using wood and nails we salvaged from the collapsed barn of eschatology.)

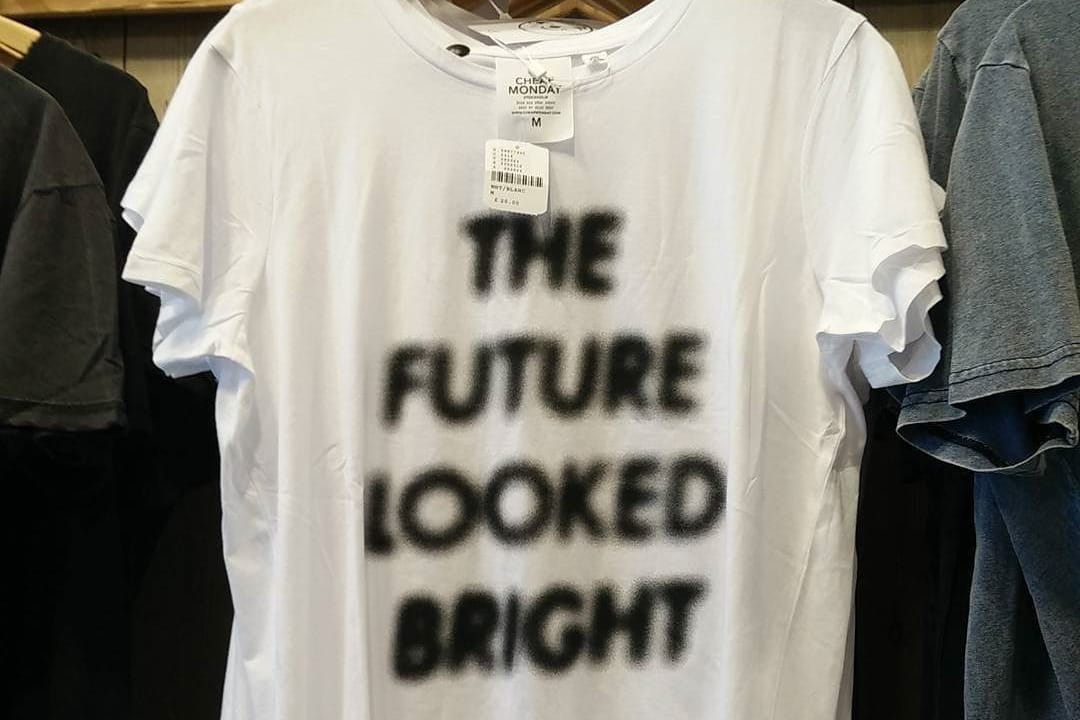

More to the immediate point, "The Future" is dead.

"The Future" was always already a story—a generic form whose basic premises and promises have been periodically reupholstered with the very latest technological gimmicks of the moment.

But the story is dead—and we all know it, too. That's one of the reasons that we folk of the West (or the Global North, or the developed nations, or whatever you'd prefer we call it) have been in such a state of existential funk for over two decades: we are mourning "The Future".

A person of around my age and older—i.e. anyone born prior to 1980 or so, and/or anyone of sufficient age to be what we now rather euphemistically call "a decision-maker" in society or business—has spent their entire lives immersed in a propaganda of "The Future". Moonbase holidays! Flying cars! Automated cities and robot servants!

But all these tokens of "The Future" are a century old or more at this point, as any scholar (and most writers) of science fiction would tell you. The tired tropes of tomorrow's world are worn thin from overuse... but they are familiar, they are comforting, and they fill a conceptual void in a way that saves us from having to think too hard.

The real object of the verb "to future", meanwhile, is neither familiar nor comforting.

What we study or work with when futuring is not "The Future", nor even the future, but rather futurity.

"The Future" is indefinite, but the circumstances in which we currently find ourselves, and the ways in which they might cash out, can nonetheless be usefully speculated upon. Therefore, rather than thinking of "The Future" as some predetermined or even predestined destination toward which we are headed, we should think instead of futurity as a field of plural possibilities, shaped by some factors under our control as well as by some factors far beyond it.

Futurity is not a place, nor even a direction of travel—which is why "number go up" is "The Future", and has in fact always been the very essence of "The Future". Rather, futurity is the possibility of change—not even the promise of change, but merely the possibility. Futurity is the understanding that next year may not necessarily be largely the same as next year.

And that brings us to the second question with which this essay is concerned: what is the subject of the verb "to future"? Who (or what) is it that does futuring?

This second question may seem either trite or obtuse, or perhaps both at once. "People do futuring, Paul, duh?" But that's precisely it: we are the subjects of the verb "to future"; we do futuring.

Yes, that "we" is problematic in its assumed generality. Matters are improving, due to the hard work and activism of many people, but historically the "we" that did futuring—even the good, plural futuring, which has futurity as its object!—has not been very representative of the "we" that that encompasses all of the humans on Starship Earth.

It is good and important that the "we" is being broadened, though we should by this point be wary of the assumption that representation is an end in itself, rather than a means to a direction of travel. (Indeed, to no small extent, representation has become increasingly imbricated into "The Future", as its marketers have sought to paper over the spreading cracks of disillusionment.)

More importantly, though, it matters that people are the subject of the verb "to future", because this should remind us that futurity is intensely and inescapably subjective. Indeed, that's exactly where its plurality comes from! This is not due to differences of opinion upon some presumably objective truth, however. On the contrary, it's an ontological claim: there will be as many futures as there are people who will end up living them.

This is why representation cannot be an end unto itself: no panel or board of people, no matter how carefully balanced and representative, will ever be able to future for everyone. The numbers just don't work! The answer to biased futuring is not to change the make-up of the elite group that does futuring, but rather to normalise and democratise futuring as an activity embedded in human life at every scale and in every location.

So, OK: we know that futuring is something that people do, and that the thing to which futuring is done is futurity, viz. the field of possible difference plotted against time.

It is tempting to detour into philosophy at this point—and I fully intend to do so at a later date, after I've set out more of the basics (and when I feel a bit more confident in my ability to publicly kick around the ideas of people far smarter than myself). But for now let's just agree that, for there to be difference, some number of things must change.

We increasingly understand change as perhaps the only constant in the universe, thanks to scientific ideas like natural selection, geological deep time, cosmology and so forth. (Perhaps that's the root of the anxiety that made "The Future" so successful a product?)

We're also realising that there are different scales of change, and that those scales are interlinked in ways that we are only now beginning to confront: "the climate" has always been changing, of course, and that change has always been a sum function of the consequences of the actions of all the things that together make up "the climate", very much including us humans.

These realisations are, if you'll excuse the earthy vernacular, a bit of a head-fuck. We're increasingly at individual risk from the consequences of a collective error, but our individual efforts to address the error or the risks serve only to make us feel powerless. Yet it was billions of individual actions combined which formed that collective error, was it not?

There are many implications and conclusions one might draw from this. Here are just two.

Firstly, futures work only appears to be about time; it's really about agency. "What will happen tomorrow?" is a much less vital—and, if you ask me, much less interesting—question than "who gets to do what?" Anyway, you have zero chance of answering the former until you answer the latter.

(Incidentally, this is why "The Future" had a pretty good predictive record for a short while, during the period when the question of "who gets to do what?" had some clear but very ugly answers.)

Secondly, technology is a sideshow. This is not to say that the things we make and make use of are not crucial elements in the story of what we do and how it changes. Nonetheless, technology is not the subject of the verb "to future"; technology does not do futuring. Nor is technology the object of the verb "to future"; futuring is not done to technology.

Which leaves us with a new question: why, then, does a casual glance at the corpus of futures work give the impression that technology is both the subject and object of the verb "to future"? Furthermore, how might we start rethinking the relationship between what we do and the things with which we do it?

In the weeks ahead, I'll be putting forward some answers to that question, and more. In the meantime, if you've got questions or answers of your own, do get in touch—whether by email, or through the comments section on the website.

Comments ()