it isn't the phones (but it isn't not the phones)

Let's clamber into the express elevator with Karl Schroeder, and have a little think about EVs and the Doomscroll. Mind the doors!

If you have an interest in worldbuilding—and given you're reading this website, I guess you must do—then you should know the work of Karl Schroeder. A singular science fiction (sf) writer and a practising futurist of no mean standing, Karl has forgotten more about worldbuilding than I will likely ever get the time to learn.

Karl's latest newsletter discusses what he's calling the "express elevator" approach to foresight, which takes its name from a slang term in the 1970s head scene: to "ride the express elevator" was to take uppers and downers at the same time.

Karl's point here is that both sf and foresight have a tendency to black and white thinking: we will end up in either a glorious utopian wonderland or a bleak hardscrabble utopia. And there's a reason for that:

The sad truth is that coherent, single-message futures are easier to understand. That’s why there are more of them. Full stop, end of story. They’re easier to dream up, easier to flesh out if you’re worldbuilding or developing a scenario, and they’re easier to explain. “It all goes to shit!” is a concise enough description of the year 2050 for most people to nod their heads and get right into the action.

But the real world doesn’t work that way.

Karl goes on to discuss the coalescing of camps around these positions, the seemingly inevitable (and exhausting) partisanship of social media... but, crucially, he's not putting all his chips on red or on black. Rather, he's inviting us to think about the mechanics of the roulette wheel itself:

... EVs are either The Answer, or they’re a failed attempt by Big Government to jam a green ideology down our throats. And it’s not that the truth lies somewhere in the middle; both of these perspectives could be right. What I object to is thinking that it has to be one or the other.

Karl takes a bit of a side-tangent here into theories of change, and particularly into what he labels as a misreading of Hegel, because he wants to be clear that what he's advocating here is neither the empty seriousness of centrism nor the handwavium of "synthesis".

I will return to the topic of theories of change in a separate essay, because it's a topic very dear to my heart. For now I will note that I mostly agree with Karl, but I think that the "synthesis" he's describing is very much the reduced Hegel that is passed down through the more vulgar Marxisms. I would argue that Karl's "express elevator" model is in fact a dialectical synthesis, and indeed bears a huge similarity to the notion of the critical utopia as advanced by utopian studies scholars since Tom Moylan's groundbreaking work on the USian New Wave authors of the 1970s.

(I have written about this quite often elsewhere, albeit mostly in an academic mode.)

Karl's example issue for the express elevator analysis is EVs, but I found myself instantly mapping the same analysis onto another hot-button issue, namely The Doomscroll.

Everyone knows this one by now, so feel free to sing along at home: rates of depression and other forms of chronic psychological distress are unprecedented, particularly among young people; with a bit of historical statistical analysis and a whole lot of common sense, it's totally obvious that smartphones are the cause of this problem!

That's one position, anyway. The other position would say no, no, no—Jonathan Haidt is mistaking correlation for causation, here; sure, The Kids spend a lot of time on their smartphones, but they're using the dopamine machine as a palliative for the experience of growing up in a world that's widely reported to be going to shit, and in which they're not allowed to go out and do anything (even if they could afford to do so).

Like Karl, my objection is increasingly not to one position or the other, but rather to the tacit assumption—which, it bears noting, is shared by both sides of the debate—that only one position or the other can be correct.

I think part of the problem here is a weird quadratic entanglement of ideological assumptions with positions on specific issues. With apologies for the very reductive read, but we could say that Haidt's "it's the phones" is the behaviourist-individualist position, while the palliative position is structuralist or social-constructivist; these overarching theories have traditionally been aligned to the right and left wings, respectively, but on this issue (and others) people are finding themselves unexpectedly in alliance with people from the "other" side of the spectrum, which results in emotional discomfort and attempts to explain away contradiction.

(This, in turn, reads to me as a harbinger of enantiodromia, which is a term I will explore in detail when I return to the topic of theories of change.)

Again, Karl's position is useful, because it refuses to accept either position as absolute, but it also refuses to discount either of them entirely. As he notes:

The express elevator does not resolve the contradictions, we don’t achieve some magical overview where decarbonization and more microplastics somehow cancel each other out. Instead we’re left with an unalloyed good and a big mess, both at the same time. These ideas don’t converge, they’re centripetal, propelling us simultaneously in two directions. That’s the nature of an express elevator. Instead of an expression of dialectic, it’s a nod to complementarity—the idea that in the real world, you sometimes have to use two or more mutually exclusive models to understand something.

Hence my title: it isn't the phones, but it isn't not the phones, either. Neither the behaviourist nor the structural models can give us a complete picture of reality; no theory ever can.

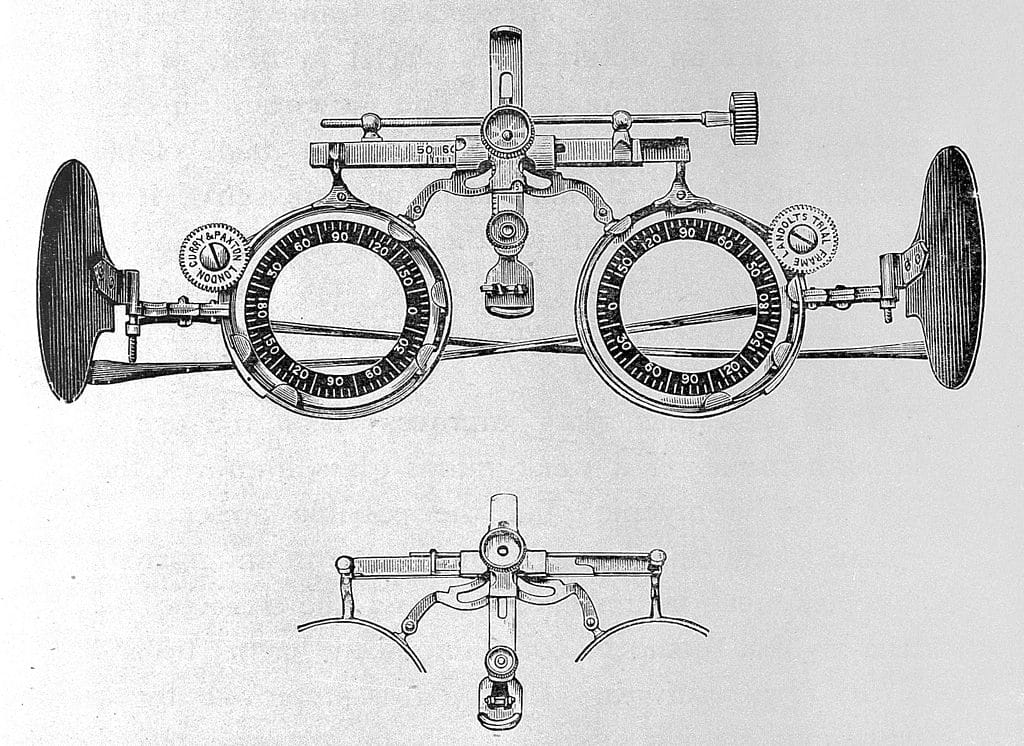

I think of theory as being like those things they put on you at the opticians when you go for an eye test: you can slot and twist a whole array of different theoretical lenses in there until the thing you're looking at comes into focus.

(The crucial thing is never to subsequently assume that you're looking at the thing "as it is"; this is what Saint Donna calls the "god trick", another topic that I will be returning to in times to come.)

The arena where this issue really grinds my gears, though, is that of climate change—to the point that I even have a routine about it. Nowadays, if someone asks me "will climate adaptation be achieved by individual consumer choices, or by structural changes shaped by state regulatory mechanisms?", my answer is always "yes".

(Read it again, slowly.)

The time spent in partisan debates over which of the two theories is the One True Theory is time lost—time with which we could be acting on the basis of what either or both theories can tell us about the world. And again, this is not centrism! Centrism is neither a plea for dialectical synthesis nor for the "express elevator", but rather the suggestion that the status quo would be fine, if only it were being managed by the centrists.

Centrism, in other words, is the politics of the business school and the boardroom.

Politics aside, Karl's observations about the "express elevator" are generally applicable to any sort of foresight or worldbuilding work—though you might want to ask yourself what sort of client you're working with before using that particular metaphor, perhaps!

(The irony here being that, were you to see myself and Karl stood next to one another, you'd quite reasonably assume that I would be the guy drawing on drug-culture metaphors to illustrate his points...)

As mentioned above, I'll be writing more about this sort of stuff, and about theories of change—cod-Hegelian and otherwise—here at Worldbuilding Agency in times to come; I will also be publishing an interview with Karl! In the meantime, you can (and should) be following the man directly.

Comments ()