worldbuilding from the shoulder: an interview with Bruce Sterling (part 2)

It's finally here! The keenly anticipated second part of the Worldbuilding Agency interview with pioneering cyperpunk ideologue turned design critic and tech-art curator, the one and only Bruno Argento...

Welcome back for the second half of my 2024 interview with OG cyberpunk turned design critic and tech-art festival director, Bruce Sterling. (The first part is here, if you missed it.)

In this back half of the discussion, we explore the role of historical fiction in the construction of various nineteenth-century nationalisms, the relationship between historical fiction and science fiction, the paradox of archiving past futures, the pragmatic utopian leanings of the Turinese... oh, and worldbuilding, of course!

Paul Graham Raven: So while you were talking about the historical knife [note: see the previous part of this interview], and also Turin’s ersatz medieval village, it reminded me of something. I was listening to a podcast hosted by the science fiction author Ada Palmer, with a colleague of hers who is also a Renaissance history expert. A lot of it went way over my head, because I don’t know a lot about the Renaissance to start with, but both of them are writing academic texts on the Renaissance in a kind of overview sense, and both of them are saying how they’re confronted with the fact that the first thing you have to do is tell the audience that everything they already think they know about the Renaissance is mostly a fiction. And I forget the exact line, but you know, it was something along the lines of “the Renaissance actually started in the Victorian era”, because the Victorians needed something they could point to in order to trace a lineage backwards.

So if we think about the trend work involved in futures—I mean, you’re taking a bunch of plots through time and you’re drawing back that kind of line-of-graph through them, and making a narrative argument about what’s happening through history. I’ve made the case that it’s an interesting to go from science fiction to futures work and then back to literature again with that idea of worldbuilding, because all of a sudden it means that historical fiction actually has way more in common with science fiction, right? Because we are in both cases extrapolating a world on the basis of what we know in the present.

Bruce Sterling: Walter Scott being a great example. Walter Scott wrote historical fictions—you could even make the argument that he invented the notion, you know, historical fiction as a genre. And the novels, they’re written anonymously, by the way—they didn’t put his name on those.

Washington Irving did the same thing, he didn’t want his name on his first books either, taking a cue from Walter Scott. He was writing under the pseudonym Geoffrey Crayon, ‘cause he’s a guy with a sketchbook—he just wants to write sketches, you know. He’s a gentleman! He’s not writing books to make money.

And neither is Walter Scott. I mean, he made a ton of money, by the way—but Walter Scott is basically, you know, a laird. He’s like the justice of the peace in some region or whatever, who somehow becomes interested in dramatizing these antiquarian things… and he dramatizes them with methods and techniques that nobody has ever applied to the past in that way before. I mean, it’s not like a startling innovation—there’s a lot of precursors of Walter Scott, but he’s the first one that really hits with this bullet-like national romanticism that then dominates the C19th in a low and an alarming way.

And that’s absolutely all over the Italian landscape, because they’re super, super into nationalist romanticism in the C19th century and the Risorgimento. And not only did they not have a Renaissance—because they didn’t make up the name, some French guy did—they didn’t even have an Italy! Italy was just a peninsula, there were no states. It’s just a bunch of balkanized duchies and, you know, weird Vatican cities and peculiar republics of San Marino. So in order to have in Italy with a tricolor flag to salute and go die for, they had to invent all this stuff... and a lot of that work was done by novelists.

Like Alessandro Manzoni. He was sort of a disciple of Walter Scott’s, but he wrote this novel of Italian national heritage called The Betrothed, or Promessi Sposi. Boy, did I ever learn a lot from that book. Must have read that thing eight times! Really, it’s a world-class masterpiece. But it’s also the first novel written in contemporary modern Italian, as was opposed to Tuscan or Venetian or some bizarre dialect. He’s a Milanese guy, but he’s actually writing literary Italian; the way he’s putting nouns and verbs together is modern Italian, he’s inventing the language as he writes the book.

I mean, he wrote one version of it in his own dialect, and then reworked on it for seven years to make it more like actual Italian. The first one was a mega hit, but then the one that he Italianized was an ultra mega hit, and nobody ever reads the first one anymore. And it’s now like 150 years old, and it’s set 200 years before he was writing, and it’s super interesting to read this thing as this historical artefact: he’s writing about Italian history for his contemporaries, but now the book itself is a historical artefact, which is almost as far back, right? When you’re reading it, you’re getting this futuristic, almost science-fictional mind-stretching thing where you have to, like, cast yourself back to what he’s saying, and then further cast yourself back to the things that he’s talking about from his own historical perspective.

So you’re rocketed through time over a period of several centuries, and the effect is very invigorating. I mean, it’s difficult in some ways, but once you sort of get into the rhythm of it, it just gives you this kind of binocular style perspective. It’s like really, really kinda good. Italo Calvino says the classics are books that you reread rather than read. I’ve read that book many times because every time I read it, I understand Italy better. And I’ll probably read it again.

PGR: The Italy that it allows you to understand better, if I understood what you were saying earlier, is to some extent an Italy that was constructed by that book as well?

BS: Yes, it’s a cultural construction project. And he had disciples like his son-in-law Massimo d’Azeglio. He’s from Piedmont, he was a politician and a novelist. I’ve read his books too; they’re not, they’re not as good as Manzoni’s books, but because they’re not put together as well, it’s kind of easier to understand what they’re doing. You can sort of imagine yourself writing a thing of that kind. And I’m very familiar with d’Azeglio—there’s streets named after him here, I’ve read his memoirs; he used to live a couple of blocks over yonder. He’s an archetypal Turinese figure, this dutiful aristocrat, doing his level best under extremely difficult circumstances and, you know, all these hidden woes and troubles.

But he’s a lucky guy in some ways, because he managed to retire as a politician as opposed to just getting hanged or beaten into disgrace. He just wanted to paint paintings and write novels, to be this kind of languid aristocrat, almost like a Benjamin Disraeli—extremely bright guy, but he wanted to be a creative, and instead he got heavily involved in politics, basically through no fault of his own, and did a pretty good job as a politician. Then he basically retired to the archives. And I understand what happened to him, and I also understand the Turinese perspective. It’s dutiful and gentile, as the Turinese would say. And you get a lot more done with a kind of gentile approach than you would by haranguing them or, you know, trying to light a fire under their feet. You want to take this kind of courtly approach, right? A lot is left unsaid.

PGR: Doff the hat, smile nicely, say nothing, that sort of thing.

BS: Yeah, I think that counts for a lot. I mean, they’re a very patient audience, the Turinese, but it’s also because they’re more interested in your gestures than in what you’re actually saying. If you see power brokers meet within Turinese society, they almost always discuss food. That’s their light chit-chat; they’re not going to say “oh, did you hear that so and so slept with so and so’s wife,” no, they’re going to talk about like noodles. It took me like forever and a day to figure that out. You’re not going to talk about anything but noodles to this guy, because he’s your enemy, right? I mean, if you start talking about what it really means, it’s going to be Capulet and Montague stilettos—somebody’s going to get hurt. But they also have this very thick layer of cultural reference with which they can, what’s the right word? Lubricate—they can lubricate their circumstances.

I mean, they get a lot done. They’ve had tremendous failures here. Like, the town’s a mess—I mean, there’s so many dead factories here, you know, it’s just fantastic. But the upside of the dead factories, to the extent that there is one, is that there’s cheap rent—so you can put on festivals or do a lot of stuff, start a business, and you’re not being strangled to death like people in San Francisco, you know. You actually have a little leftover money where you could do some proviamo style activities. I have high hopes for them! I’m very, very engaged in what they’re up to. To know them is to love them, really.

PGR: I definitely get that sense from you—that you have an almost avuncular care, it seems.

BS: You know, they asked me to come, and I didn’t really expect that at all. It’s like, why don’t you come in and be the curator of our art fair? I’d never heard of their fair! I’d been to Turin, but I knew scarcely anything about it. It’s more like, okay, why not? Why not just go? But the fact that they asked makes it a lot less imperialistic—it’s not like I’ve shown up here to tell them what to do. On the contrary, I think it’s had a calming effect on me, a kind of a broadening effect. You know, I don’t spend a lot of time cyberpunking out in Turin, although they’re very, very aware that I’m a cyberpunk writer; they consider that romantic. My activities here are more cultural—they’re about art and design, and about technology, methods of production; stuff like open source hardware. Fab labs are like standard Bruce Sterling habitats in Turin; next to the laser cutter and the 3D printer, you’re gonna see a lot of Sterling there.

PGR: Is it not more the case... it’s not that you’re not cyberpunking out there, it’s that cyberpunk has become enough of the fabric of things that, you know, that stuff’s just there now.

BS: Yes, it is—it’s old-fashioned. In my stay here, I’ve been donating a lot of books to the local MUFANT, which is the Turinese Museum of Fantascienza, which is ten years old. You know, I turn 70 next month; I could wake up dead some morning. So if I don’t give them this cyberpunk heritage, all these Bruce Sterling first editions of associative clutter, it might just get tossed into the street. I mean, I actually have to archive it to be aware that it has a cultural history in the future. By dealing with a science fiction museum, you’re kind of embracing the oxymoron, there—I mean, a science fiction museum, how would that make sense? Like a museum of the future. But I was like, okay, everything ends up in the museum. Everything.

PGR: On museums of the future, very famously there’s one in Dubai, which is where they hold the big futurist conference every year…

BS: It’s not much of a museum in my opinion. That’s more, you know, a futurist show place. If you go there, it doesn’t actually have the history of futurism in it—a history which is very extensive, by the way.

PGR: Yeah, it is. I spent a lot of time engaged with the history of futuring during my academic work because, again, that question of method, but also that question of origins. There’s some really good work by a guy called Andrew Curry, he wrote a great chapter for the Handbook of Social Futures, an account of the development of futures work basically from RAND onwards, but really focusing on the schisms... because it’s not that there weren’t always more creative and qualitative approaches to futuring.

There was the post-RAND paradigm, the intuitive school—the stuff that goes on to be picked up by Shell and everyone else, which was very much focused on the idea of, okay, here’s all this reconstruction money, this Marshall Plan money for Europe, maybe we can do something interesting with that? Like, here’s a big pile of money to play with. On the other hand, there was another school who were like “hang on a second, but what are the social problems here?”

So you get, very early on, that split into on the one hand futurism with a focus on what’s next year’s big selling tech thing, that products and productivity focus thing, but on the other side, that more utopian approach. And the loadedness of the term utopia is, is in a way, an indication of how that went—you know, that sense that if you speak about utopian thinking now, it’s largely a pejorative.

But if you talk to people in utopian studies, there’s so much more nuance to it—you know, there are certainly still pie-in-the-sky utopias, but simply to be able to aspire to a future in which something other than how fast our computers might be has changed, that shouldn’t seem as radical as it sometimes still does.

There’s that sense in a lot of mainstream futurism up to basically the end of the 90s—and in parallel, really, with a lot of science fiction of the time—that sense that, you know, society is here and technology is there, and they change at different rates, and there’s obviously some interaction, but largely they’re separate. And I think that over time, in more recent years, we’ve had this kind of drawing together, where these two things are seen as inextricable.

BS: Well, here in Turin, we’re about to have a festival whose title is Practical Utopia.

PGR: Oh, really?

BS: Yeah, I’ll be speaking there.

[Note: the transcript of Bruce's talk can be found on Medium.]

You know, utopia in the Italian language does not have the pejorative atmosphere that it does in English—mostly because it’s an English word, it’s not an Italian word.

PGR: I think it was Greek originally, yeah.

BS: Yeah, but okay, they don’t mind. And Practical Utopia is actually a rather Turinese notion; I think it’s kind of nice. They have this festival every two years. It’s not my festival, but I know the organizers and I always speak at it, the Biennale Technologia. It’s sort of like they haul the technologists out of the woodwork in Turin, and they kind of come out and do their TED Talk display kind of stuff, except it’s more folksy, you know—it’s actually festive. I mean, it’s literally a technology festival.

PGR: Again, this is a term which has become somewhat muddied recently, but from what you’re saying, it’s a populist festival—it’s not tech people talking to tech people, it’s tech people talking to people more broadly.

BS: I think it’s actually the different technical players in Italy and Torino talking to one another—but the town is so dominated by engineering and technology and academia that there’s not a lot of other people left. I mean, that’s who they are, they’re all technologists here. It doesn’t have like a big fashion scene like Milan. The Milanese think that the Turinese dress like laboratory workers, it’s quite funny. But I kinda like it; I mean, it has aspects of being welcomed as a small-town boy. But, one of the things I like best about Turin is that it’s small enough to actually comprehend, right? It’s like a hamster, like a laboratory animal. You can kind of see things working out. It’s not so huge and multiplex as studying the history of London; it’s a situation where if you know the major players and what went on, it’s physically comprehensible.

You could walk across the city in a day. Even though it’s 2,000 years old, it’s a relatively human scale, there’s not a lot of skyscrapers—you can kind of get your head around it even, even as a foreigner. And it’s exemplary in a lot of areas that I find of interest, like engineering, design, manufacturing, cultural studies. Even art stuff. I mean, Torino’s not an art powerhouse, but Torino makes up stuff like arte povera, which was big in the 60s and 70s—just making art out of like abject pieces of junk, like used bricks, knotted rope, old crumpled newspapers. That’s arte povera, that’s a native Turinese expression. As a punk, you can totally get that, you know, it’s like punk avant la lettre. And of course all the surviving ones are now, you know, absolutely the maestri. Mr. Arte Povera, like, owns his own water-mill someplace. It’s just fun to watch them, you know, they’re kind of great.

PGR: All right, I want to cycle back a little bit with what I think will probably be the last question…

BS: Yeah, and tomorrow I have to leave. I’m going back to Austin. Gotta go pick up the loose ends of Americanization here. I’m a bit sentimental about them. I’m sorry to be walking out the door.

PGR: I get the feeling you’re a little conflicted about the trip?

BS: Right. Well, you know, at least it’s not like going to Belgrade, where they actually sell cyberpunk beer right in the street. It’s not very good, by the way—I would not recommend this Serbian cyberpunk beer, from the Robo Craft brewery.

PGR: Sounds appealing.

BS: Well, it’s not for export, that’s the best part. It is like impossible to get it outside of Belgrade. I think it’s a tax write-off or a money laundry, frankly, but it just killed me to see cyberpunk beer in Belgrade, of all the damn things. I mean, the Turinese would not do that. They’re way too refined to do anything so vulgar. So, the last question here, right?

PGR: Yeah—we’ve spent a lot of time actually talking about history and the past rather than the future, and I think that’s a really valuable thing. Because wrapped up in that is the sense that with Walter Scott, with the American writer whose name…

BS: Washington Irving. Yeah. I recommend him. He’s actually quite readable. I mean, Walter Scott could be some heavy sledding, but Washington Irving, you know, kind of zips right along.

PGR: Yeah. So in both cases, and I think in a lot of the other cases—I think there’s an extent to which you can say this of Turin’s ersatz medieval village as well, and as Ada Palmer said about the Renaissance being an invention of the British Victorians to some extent—these are all, in one way or another, sorts of worldbuilding; there’s a relationship to what is being done in both science fiction and other forms of futures work there. But: all of them are explicitly political. Is worldbuilding inherently political?

BS: I think it’s as inherently political as other forms of all encompassing philosophical system-building, right? I mean, if you’re a philosopher, you’re supposed to have a very large system that kind of explains the universe. It’s not enough to have a philosophy that’s just about your neighborhood in Turin. That’s not philosophy; philosophy has to have this all-encompassing, somewhat cosmic grandeur, which is about beginnings, endings, purposes, meaning, the Right, and so forth. And worldbuilding is like an extension of that, in that you’re trying to imagine the whole world.

So, you know, if you turn that inside out, this was kind of the Julian Bleecker insight: why don’t you just build the objects in the world, instead of building the world? Build the design fiction object, the diegetic prototype, which implies a larger world, but is actually small—like a coffee cup or a beer bottle or a pocket knife, right? And I think that was actually a very fruitful and interesting approach, because that doesn’t look like worldbuilding.

It’s kind of even the opposite of doing worldbuilding—because you’re just doing this apparently simple and modest thing, but a set of speculative implications kind of boils off of it. And the same is true of like technology artwork. I mean, it tends to imply the future, but it’s from the art world, rather than a new commercial project or product. So it just kind of opens up people’s minds to other possibilities…

I used to be very fond of and interested in worldbuilding techniques, and I would bone up on how to do it, read all the science fictional things about how to create fantastically interesting worlds. But as I’ve grown older, I tend to paint from the shoulder more. I want to do something illustrative, something that doesn’t burden people with long genealogies of the elvish language, or kind of connecting things to one or the other, right? I think that’s good, and it’s kind of the way forward.

Like, one of the problems we’ve faced in science fiction writing until rather recently was the singularity problem, where there’s this notion that some AI shoggoth will bite all our legs off, and therefore it’s no use even talking about the future, because we’ll be into a posthuman situation where it’s impossible to think about it and so forth and so on.

I found that not exactly menacing, but I thought it was a creative problem that was quite serious. And my personal answer to that was, instead of arguing endlessly with Dr. Vernor Vinge—very nice guy, by the way—it would be better to move sideways, you know, to put some cultural distance between yourself and that thing, to go someplace to where somebody is having a different kind of singularity issue.

William Gibson has frequently talked about this, but all cyberpunks have this problem of writing in the C21st and ignoring the C22nd. In the C20th century it was very easy for sci-fi writers to just sort of conjure up the year 2000 or the Millennium, and people would immediately feel this kind of period space-age interest. Whereas if you’re here in the C21st, and you want to discuss the C22nd, it’s very difficult to get a foothold or actually do anything.

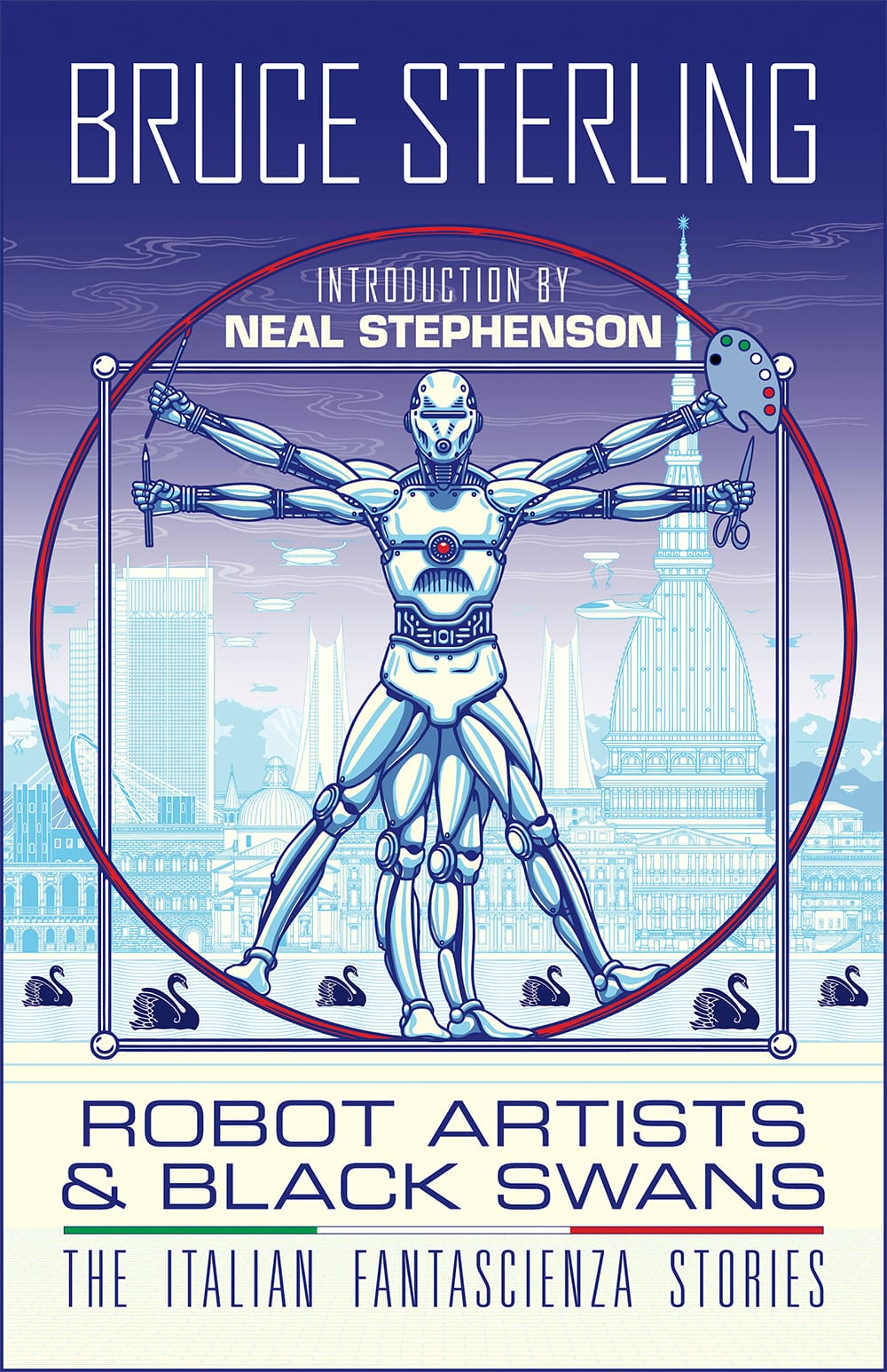

So, I’ve written this collection of fantascienza stories, and a lot of them are historical, they tend to be about Italian history. But the last one that’s in this most recent collection, Robot Artists and Black Swans, is a story which is set in the 22nd century, and it’s about a philosophical and political debate between an artist and a scientist, and I just kind of made that one up. I mean, it’s got a lot of worldbuilding, apparently, but it’s very splotchy and kind of suggestive, and almost everything in it that affects the reader is in the dialogue. It’s an extremely dialogue-centric situation where two characters who might be Romeo and Juliet are kind of talking past one another from very different kind of paradigms—it’s this kind of clash of worlds.

And I don’t want to like get into the tall sci-fi weeds here, but people who have read Robot Artists and Black Swans and reviewed it, they often find the Italian stuff rather parochial, whereas this C22nd story actually seems to have captured people’s imaginations in some way. And it’s because it’s grand and they talk about philosophy rather a lot, right? I mean, [the two characters are] advocates of different worlds, kind of, they’re both activists and very active characters who are aiming at cultural transformation, but from two very different perspectives. And yet they have this inner camaraderie, or a kind of almost erotic attraction that seems to come across.

And, you know, I don’t know if I’ll write another story like that—but most of my fantascienza stories are of interest to fantascienza people, they’re kind of unusual curios, whereas that one I think is actually represents some kind of advance. I mean, it’s actually doing something that is about worldbuilding, and it’s about futurity and it’s about topics that seem to capture people in some way. It kind of restores some of the allure that the C21st century had for the C20th, in very troubled times.

PGR: I found it really a really interesting story on a lot of levels, firstly because—and perhaps more so this year than when you wrote it—because of the ongoing questions that we are faced with at the moment, such as “what does the emergence of generative models mean for the production of art,” and so on and so forth; the human intentionality behind art or otherwise is very much in play there.

But what I found fascinating, particularly as someone who spent ten years in academia, is that so much of the discourse and the cut and thrust of their debate is really, really familiar to me, right? And also hidden in there is the the kind of transhumanism versus posthumanism thing, as well. I think what I found really fascinating was the continuity of those quite old binary divisions between various philosophies, and as such, they’re incredibly recognizable—they’re plausible exactly because they’re so familiar. It’s like, okay—it’s the C22nd century, people are still arguing about these things.

But what’s really fun is the way you flipped some of the polarities, right? It was really interesting to read, [late in 2023] when I was reviewing it, a story about a robot artist, an artificial artist in which the [human] artist character is defending the robot as a novel and unique artistic being. Which kind of makes sense in, in terms of the New Materialist position: you know, it’s just another actor in the world! But in the discourse at the moment—and speaking for myself personally, you know, as an artist, I am not greatly on Team Robot right now, because I can see them kind of eating my lunch.

But in the sense of the worldbuilding there, I find it interesting the term you used, painting from the shoulder.

BS: Right.

PGR: What I wonder is—and I’m not discounting, you know, if you say that was a choice, I’m totally willing to believe that! But at the same time, I wonder if there’s not also possibly something that comes, after many years of doing it… I guess it’s like they say about jazz musicians, right? You have to learn to be really brilliant to make it sound that easy. To worldbuild from the shoulder, you have to have done it the hard way before, in order to know where just a few dabs will do the job.

BS: How can I put this? I think the jazz musician thing is maybe is a key to it, because great jazz is not about playing all the possible notes, right? It’s syncopation, and kind of not quite being there when you want to do it—not just like bravura pieces of technical extravagance on your trombone, but the willingness to just dramatically pause, or just not do that part. Or, you know, drop it and pick it up later, with a kind of accelerated pitch. A lot of jazz is kind of empty noodling, but then there’s works of jazz that really work and feel quite timeless.

And I think that particular story, although it’s about a lot of modern topics like robot art and so forth, is one of the ones that was most likely to be read with interest by many people in different countries, although it’s very Italian. I think it’s going to last as part of the Bruce Sterling oeuvre, if anybody wants to bite on that; that’s going to be one where people say “well, wait a minute, huh?” When this is not a period artefact, it’s not really of the future or of the past, it’s just acquired this quality of Calvino-like classicism. It kind of offers more than appears on the page.

PGR: Did you set out to do that?

BS: It was commissioned by a bunch of guys in Rome, the Connectivist group. I’m on quite good terms with them, but I’m kind of the only Turinese Connectivist, and they often ask me to write things for their situation. So I thought, okay, I’m going to write something which is not in Turin; it’s mostly set in Verona and Rome. And I kind of had some deadline pressure and I thought, okay, I’m going to toss this thing off, I’m going to like abandon a lot of the nit-picky work I usually do in the basement and just kind of jump right out the window.

And I think that actually helped, right? It just has this element of... not hurry, exactly, but it’s getting its point across more suggestively than if I’d gone into all kinds of detail about the political arrangements of the characters. It also helps that the main narrative character is this kind of over-equipped swot, you know; you kind of trust him from the beginning. He doesn’t have to explain himself much because he’s always analyzing stuff, he’s a critic—so he’s kind of doing a lot of the work of the reader, right? When he’s walking around the town, he’s like looking at everything in the city and analyzing it, thinking about it in his stream of consciousness—and that means you don’t have to. He’s like a worldbuilding critic; he’s kind of worldbuilding as he looks at stuff with the Gibsonian inventory of perception. He’s sufficiently intensely observant that he kind of carries you with him.

Not that you like him. He’s just like in the business of worldbuilding, so the author doesn’t have to.

PGR: Yeah, no, he’s not a likeable character. I mean, neither of them are likeable…

BS: No, they’re quite terrible, actually.

PGR: But I think that’s one of the things that makes it feel convincingly futuristic.

BS: Well, also, although they don’t find themselves quite scary, normal people do. If the two of them, like, go into a bar together to just get a beer and a grilled cheese sandwich, people are frightened. It’s like, what, are they going to beat you up? No—but, you know, they’re heavy.

PGR: You don’t want to cross them.

BS: Yeah, it’s as if Sir Walter Scott had come into the room. And I was “who’s that guy over there?” Oh, that’s Sir Walter Scott.

PGR: “Is he... is he going to narrate us? That would be… “

BS: Yeah, what will he do? Well, he’s nevertheless kind of intimidating.

That's the lot! Thanks again to Bruce for putting up with my questions for a couple of hours (and apologies for taking so long to getting round to publishing the results).

Thanks also to you for reading along. If you enjoyed this interview, please forward the email or the link to someone else who might also enjoy it, and subscribe (for free!) to receive more such interviews direct to your inbox in times to come—they will emerge pretty much monthly, interspersed with essays and other material.

(You can also subscribe to WA's weeknotes, if you want the inside track on the life of a consulting creative and critical foresight practitioner... )

Comments ()