deliberate oxymorons: an interview with Bruce Sterling (part 1)

In the first part of this two-part interview, OG cyberpunk Bruce Sterling discusses the pursuit of deliberate oxymorons as a creative strategy, worldbuilding in the context of history and futurity, Berlusconi on the moon, and much, much more.

Author, journalist, cyberpunk propagandist, tech-art pioneer, blogger, design critic, art festival director... Bruce Sterling has been many things and nurtured many fascinations, often five to ten years before the rest of the world realised that they were even there to be fascinated by.

Coming up as an aspiring science fiction writer and tech critic during the Gilded Age of blogging, Sterling’s prodigious output and magpie’s eye for the next big thing were probably even more influential on my own work and thought than were his novels and stories. It’s my great pleasure and privilege to have interviewed him a second time (and to have asked questions that were notably less stupid this time around).

In the first part of this two-part interview, Bruce expounds upon the pursuit of deliberate oxymorons (“cyberpunk”, “luxury multi-tool”) as a creative strategy, the particular delights and travails of fantascienza, Berlusconi on the moon, Washington Irving in Granada... and (of course!) worldbuilding, as a craft that can just as easily be directed into history as into futurity. Enjoy!

Paul Graham Raven: What does it say on your business card? If indeed you actually have a business card.

Bruce Sterling: I don’t have a business card.

PGR: Okay. What’s your elevator pitch, on the rare occasion you meet someone who doesn’t know who you are already? What do you tell them you do?

BS: I would tell them nowadays that I’m the art director of a technology art fair in Turin, Italy. Even though that is not a business, I’ve never made even a euro doing that—you have no duties, and my festival is very small. But, you know, I write science fiction. I write fantascienza; I like writing science fiction for the Italian market. That’s the unusual thing that I’ve done in the current century.

Once I used to write a whole lot of science fiction, I was a successful commercial American science fiction author. I wrote a book with William Gibson that did very well, and I wrote some non-fiction books. I wrote one of the first books about computer crime, Hacker Crackdown, which was rather commercially successful and was used by police agencies to teach computer crime investigation. So I’ve done popular science, a lot of science writing.

I tend to hang out with futurists quite a lot. I knew people from Global Business Network and Monitor, and I’ve been known to be asked to consult for companies. I don’t do a lot of that right now. I mean, normally when I’m consulting for companies now, I am negotiating with Italian companies to support our technology art fair, where we do a lot of art that is based on hardware that is not dedicated for artistic purposes. And there’s a ton of that in Italy—I mean, in Italy, that’s just a given for them. You give them a Xerox machine, they want to do fine art with it.

But then you have to fund that and put it on display and explain it to people and write the liner notes and put the card on the on the wall, and so I do a lot of that now, once a year. I’ve been here in Turin long enough that I know everybody else who would want to do that. So I guess I would count as their gray eminence in some ways. I mean, I’m among the oldest people in my milieu of techno-art futurists here.

PGR: As I understand it, that’s almost a kind of return to something you were doing very early on. You were very involved in, I don’t think it was called that then, but the tech-art scene in Austin [Texas] when you were younger, right?

BS: Yeah, I used to hang out with a lot of robotics guys and engineering people, software people and hardware people. I mean, my father was an engineer, so I have a long lasting interest in material culture and how things are made. It was very rare of me to actually do any of that. But now in later life—I mean, this year I turned 70, and I’m actually giving in and doing a lot more hands-on... well, I don’t even like to call it creative work, really.

But I’m very involved in studies of luxury multi-tools. [brandishes multi-tool] This is the Leatherman Free from the USA; as an American in Italy, it’s kind of like a crusade of mine to try to explain to people why an object like this existed, why you might want to use it, and why an American invented it in Eastern Europe. We’re known for distributing tools to our guests and the core of creative artists that surrounds our festival. I found that I could give them like a futuristic lecture about what to do, but they were much, much more interested if I just said to them, “if I gave you this, what would you do with it,” right?. I mean, I’ll put it in a bag—you can have ten! And then they come back and we put what they did on display.

That’s just an intervention that the Turinese invited me to do, and nobody in Austin would have asked me to do such a thing. But in Italian design circles, they have the atmosphere, or the motto really, “proviamo”: give it a shot, prove it, try it out. And proviamo is never just a lecture; proviamo is always a thing. It’s a process or a tool—you know, make a lamp out of plastic bags, make a chair out of styrofoam. That’s a proviamo, very Italian design-centric situation. So I do a lot of that.

I mean, I’m the judge, I’m the art director for our fair. And people come up with these proviamo “innovations”, or just hacks, really. Interventions, you might call them. And I have to judge them and decide whether to show them to the Turinese public, right? So in order to do that, I have to have an aesthetic, and I have to have some idea of what’s worth showing to the public. I mean, we’re publicly funded art fair, you know—it’s my job, really. And so I do a lot of writing for this festival; I write all our pamphlets, do a lot of basically behind-the-scenes art-world politics.

But, you know, I found that this suits me—I find it less tiresome than actually going out and doing futurism for people and getting paid for it. I mean, that situation, which I’ve done a lot, it is like politics, but it’s also kind of psychoanalytic; you’re dealing with people who are in trouble, and you’re trying to sort of gently bend their worldview so they could see some way out of their difficulty. Whereas something like brandishing a Leatherman Free multi-tool on an Italian actually gets to the point, and it stays in his pocket when you leave the room.

PGR: We’ve jumped ahead in a really useful way, with that distinction you’re making between the intervention you would make for a corporate client seeking a work of futurism and design intervention aimed at the public. I gather from what you’re saying that there’s a particularity to the Turinese, or perhaps just maybe Italians in general, but there’s clearly a difference between those two audiences, even as there’s clearly something similar about those processes. Can you talk to that connection? What is similar in those two processes?

BS: Well, you know, futurism, it has a craft—and there were a lot of people who were involved in futurism who were also involved in things like Whole Earth Review and Co-Evolution Quarterly from California in the early days of Silicon Valley, which had this personal-computer philosophy of access to tools and ideas, which sort of linked somehow with a punk-DIY ethos of the 1970s. That was a scene in Austin at which I was very heavily involved, being a cyberpunk science fiction writer. So I was always interested instead in asking okay, what happens if I just seize the means of production and do it myself? Or what happens if I write something and it doesn’t seem to have any commercial application, or any genre in which to put it?

Or what happens if I pursue things that are deliberate oxymorons—like cyberpunk, right? When the term was invented, it was literally a contradiction in terms, and that tends to open up spaces: creative spaces that you can’t see. I’m always aware of those, and I’m aware of the artefacts that surround them—the kind of verbal formulation, or the worldbuilding aspects, the artefacts of a built world, like design fiction artefacts within an imaginary world, right? There are a lot of those around. Sometimes they win prizes at our festival, like Christoph Laimer’s 3D printed Swiss clock. This is a prototypical festival hit, because it’s literally like a C17th Swiss escapement clock that the guy printed out in his basement with a homemade 3D printer. He brings it over in a case, and you wind it up and it ticks; it’s actually a clock.

I mean, the guy’s a clock designer by trade; he’s just a 3D hobbyist. But he made this thing where even the springs are made of this horrible 3D-printed plastic. And if you know anything about 3D-printing or anything about clocks, and you’re looking at this thing, it’s like really just kind of a technological advent. Okay, it does not tell time properly; you know, humidity messes with it, dust jams the gears. As a material for making a clock—a real, functional, well-engineered clock—3D-printed plastic is one of the worst things you could possibly use. But, as an intervention that shows the potential, shows the intricacy of this unusual method of additive manufacturing? The Turinese are just absolutely fascinated by that; they’ll line up around the block for an artefact like that.

It’s a manufacturing town, Turin. It’s the home of Fiat, the car company. It was the first and biggest industrial city in Italy in the 19th century; it had telegraphs, canals, railway systems, long before anybody else. Factory assembly lines, Fordism, it was all going on here. It’s like a Detroit that didn’t die. I mean, it almost died—it lost a third of its population in the 70s. But it sprung back to life, and it kind of advances with this proviamo method that I’m describing, and that’s why they fund our little festival. I’ve been here for, I don’t know, since 2008, on and off. I have legal residency, but I’m not Turinese. I just enjoy hanging out with them because they give me unusual opportunities to mess with people’s heads. I don’t hesitate to take advantage of those opportunities, but telling them sci-fi stories is not the most effective way to get under the skin of Turinese culture.

PGR: So what is it about science fiction that, for some people in some places at some times, does or has worked better? Or not? You raised the word worldbuilding in your answer there; one of the things that fascinates me about the term, and one of the reasons I’m curious to speak to more people about it is, is that some people—particularly in the design world—seem very willing to accept, you know, when I say to them, “oh, okay, you’re doing a form of world building here,” they’re like, “yes, absolutely.” And I think I get that vibe from what you were saying earlier.

But other people are very resistant to that idea, because it smacks, I think, of a comparison. People feel that I’m saying, “oh, you’re doing design fiction, therefore you’re doing science fiction.” And I totally recognize that they are not the same thing! Not least because yourself and Julian Bleecker both insisted on that very, very early in the process of the popularization of design fiction. But at the same time, there is definitely a really important commonality in there.

So, leaving aside the, the whole M. John Harrison style discourse, which interests me as a writer—

BS: I’m quite the M. John Harrison fan, by the way.

PGR: Likewise.

BS: Yeah. He’s really a serious writer. He’s probably the best New Wave British science fiction writer, you know. Superior in some ways to Ballard, even.

PGR: I have been revisiting that famous blog post of his about worldbuilding, and some of the fall-out from that at the time. And I think that what he’s saying is not incompatible with what I’m thinking. As often happens, the word “worldbuilding” itself has become loaded with certain associations, which has given it a sort of political valence almost.

BS: Right.

PGR: As a science fiction writer, one builds a world—and we can come back to the questions of to what extent, and in what way is the best way to do that. But I would put it to you that even for a designer who doesn’t think they are a speculative designer in that sense—even a designer who is like, “okay, I’m going to design a new multi-tool that will be a big seller this decade”—that in the making of that product, there is an act of worldbuilding going on, even if the person doesn’t necessarily think of it as such. And that process is in some way closely related to, if not exactly the same as, the process involved in the building of a science fictional world.

BS: Well, you know, I think that you’re right that these terms kind of get crusted over. I mean, somebody would invent a term like worldbuilding, and then other people would realize that it was potentially useful, and there’s like your Cambrian explosion of method where everybody tries to figure out “what’s in it for me,” right?

And I agree that that gets in the way, you know, especially if you’re trying to actually sell it and make money doing it. It’s more easy to be effective at changing people’s attitudes or minds if you don’t require any recompense or fame or power for doing it, right? And if you just show up and mess with them, they’re actually much more affected than they are if you say “read this short story of mine, and please buy my short story collection.” It just tends to get in the way.

But if you go to a different society—and, you know, I’ve done that since I was a teenager—you can escape the limits of the English language. Like, in Italian, worldbuilding doesn’t really make very much sense; it’s a neologism that never really got any grip here. They nevertheless do a lot of building in very unorthodox ways. Here in Turin, they have the Borgo Medievale, the medieval village, which was the first pseudo-medieval village ever built in the world. It was built in the 1880s by a group of arts and crafts enthusiasts; they were having a national fair, and they said “let’s just build a replica medieval village, and we’ll have everybody dress up in costume and we’ll serve medieval food and it’ll be part of the fair.” Then they went out and they found the best archaeologists and sort of mapped out this exquisite medieval village, which is still standing there.

So that’s a worldbuilding exercise by Turinese standards, right? I mean, you’re rebuilding a heritage structure; it’s actually the first structure that’s deliberately invented for an Italian heritage industry. Not actual heritage, but a heritage industry where you have to pay. I mean, they come up with the tickets. Where’s the heritage? In Italy, there’s heritage all over the place. That’s like hundreds of years of debris. How do you put like a circle around that and say “okay, this is the little world,” and then you come in and you have this transformative experience, and then you buy stuff at the gift store and everybody’s happy. That’s an actual kind of mini worldbuilding scheme, right? And it has an economic base and it has an ideology, and also it’s intensely patriotic.

I mean, the Italian heritage industry is a very big deal across Europe. Everybody from Europe comes in to see, you know, Fiorenza and the work of Brunelleschi, to take the gondola. The place is littered with UNESCO World Heritage Sites! And every one of those World Heritage Sites is somehow detached from economic reality, or its original purpose. It’s broken loose, and it can’t possibly be what it once was—like, a royal palace? Okay, there’s no royalty. A nunnery? Okay, there’s scarcely any nuns left.

But commonly they’ve had a lot of foot traffic, they look very nice. I mean, they’re well put-together, you know; a lot of money is spent maintaining them, there’s all kinds of economic activity going in there, you know, specialized food, t-shirts, bumper stickers, snow globes, keychains, books. Some kind of app, right?

I understand that process very well now, because I’ve been involved in it. I understand particularly well how it works here in Turin. I don’t give them a lot of advice, but this past year, after two years of pandemic, there was more art on display in Torino than I’ve ever seen; the streets were just flooded with art enthusiasts. It looked like Fiorenza, it looked like Florence, you know—which is an incredible transition for a very gritty, heavily polluted automobile town, right? They’ve actually remade themselves. And they don’t even make that much art! I mean, I’m always encouraging them to do more; they’re not particularly interested in it. They’re actually a lot more interested in manufacturing and engineering, and the kind of things that you might see at the Politecnico. Also, they’re political.

But, you know, I find that my involvement with this intervention actually called on a lot of my futurist instincts. And when I talk to these people, players within the local cultural scene, I almost always address them as a futurist. It’s like “this is the trend line, and this is where it seems that it might be going.” But I don’t dress up in my futurist wizard hat, right? Instead, I tend to say things like “well, this building, you save this building, and then you save this other building. And that tactic didn’t work, but this tactic seems to be doing great, and I especially like this one over here.”

That’s a thing you can say as a foreigner, because it sounds flattering—you know, this strange guy came in and he said we were doing great! But also I just learned a whole lot by doing it; I’m just vastly better informed about art and technology than I was when I arrived in Europe. I mean, I’ve been in Europe many times, but I came to stay more or less at the turn of the century, and it’s really been kind of a sentimental and moral education—sort of back to the Old World.

I mean, I like the parts of the Old World that don’t work, and I like the parts of the Old World that don’t yet exist, but also I just like the way that the passage of time has sort of opened up for observation. Like here—[brandishes knife]. This is kind of a weird Italian counterpart to the multi-tool I was brandishing earlier. This is a historical Piemontese pocket knife—you know, every province of Italy has a local heritage pocket knife, right? So this is called a barachin. It’s native to Piedmont and it’s a farming tool; it’s mostly used to trim grape vines, because they’re big wine producing region. It’s just dead simple; it’s a piece of olive wood with a piece of hand-hammered iron, and it’s got this thumb latch that you can hold on the back, and that allows you to slice up your grapevines without taking your fingers off, right?

So for a long time I was searching for a historic barachin—and they don’t exist, because they’re just crappy farm tools. They all rusted; nobody had any reason to valorize them. Until recently, guys like this guy here, Daniela Mauro, who’s a craftsman, started making museum-replica farm knives. So it comes with a little certificate of authenticity, and it’s in this nice rural-looking burlap pouch. And this thing has next to no agricultural function—I mean, it’s a cultural artefact for the tourist trade, and for Italian patriotic heritage people. He made it with his best efforts to be a historically accurate barachin. I mean, it really looks like one! It’s a little bit more glossy because he’s got a better level of sandpaper than a farmer would have. But you know, as a knife, it’s a piece of crap—I tried to do a little knife work with it, it was immediately flaking and cracking. I mean, this baby here [brandishes Leatherman] will eat the lunch of this pathetic thing a thousand times over!

But [the barachin] has Walter Benjamin aura, this is like an actual mystical object, which used to be one of the crudest and dumbest things. Homemade piece of iron, right? These are like poles of Turinese culture here, right—one’s on the one pole, the other’s on the other, but they have more in common than you would think, because they’re both moving toward luxury and away from actual utilitarian function.

I mean, a thing like [the barachin], when it’s really used, it’s more or less a torture implement. You’re out there working on your lousy farm, trying to get by, and you’re at it from dawn to dusk, slashing your way through the grapevines. You’re poor as dirt, you’re shoeless, you’re not educated. You’re a literal Piedmontese 17th century peasant. This dates back to the Thirty Years War! It’s not a cute, fun thing, right? And a thing like this, it’s so elaborate and so Baroque and so over designed that it’s verging on luxury multi tool.

In fact, the trend is toward luxury. You can get gold plated ones, right? So there’s something going on there that is very time-based that I understand. I mean, these are not works of design fiction. This [barachin] isn’t a fictional thing; this is a historical collector’s item, and this [Leatherman] is pretty functional. It could save your life, you know, it’s a real tool, got serious tool steel.

Okay, so there’s a historical narrative here. I mean, there’s a story, right? And it’s a super Turinese story. I could write a sci-fi story about, oh, it’s that guy who’s a knife collector; he finds, like, the mystery knife. But no—I’m better off just sitting down with the artist instead, and saying, look, there’s this one and here’s that one. What comes out of that, what can we do with this? Where can we push this? I mean, what happens when [the Leatherman] is as old as [the barachin]? What does a social role look like in 300 years, how can we prepare the museum for this?

PGR: So that’s interesting, because I was looking at your Artmaker blog just this morning, and I clipped a quote from there: “Collectors of many different kinds like curios. If you’re collecting the gamut, you’re interested in expansions of the gamut.”

BS: Right.

PGR: And then you say “I’m not even sure that this is an aesthetic. It’s more like a scientist diligently searching for extreme cases in order to illuminate the phenomenon under study.”

BS: Right. So there is there is such a thing as an aesthetic with tools of this kind, and those are known as pocket jewelry. Pocket jewelry is like very high-end Italian pocket-knives that have been made by the same family for 200 years, and sometimes they have semi-precious stones; they’re basically like medieval poignards, something you carry around for the luxury of it rather than for its functionality. It’s the gentleman’s knife, and its purpose is social: it’s to demonstrate that you’re a gentleman, and that you have the knife.

But at the same time, there’s also this opposite version of luxury where something is ultra-functional, right? Not just pretty and artistic, but like super top-end blade steel with a diamond edge, whatever. It just has this kind of… well, you know, “luxury multi-tool” is an oxymoron. “Luxury multi-tool” is going into a space that’s kind of poorly understood. It’s like maker luxury, you know—it’s just lusso, which is the Italian term for luxury. And you see a lot of stuff in Italian society that is lusso that would not be considered lusso in any other society. Like lusso popcorn.

Well, for me it was like, what is it? I mean, why did you luxuriate that? Well, you know, that’s nature of Italian society—they’re kind of good at like putting this lusso aura on stuff, and just attending to the detailing of it. Like, an Italian luxury pocket knife is made to extremely fine tolerances, but also it tends to be made out of precious or semi-precious materials, stuff you just can’t get, right? Like Carrara marble. Where do you get Carrara marble? You get it in Carrara and nowhere else.

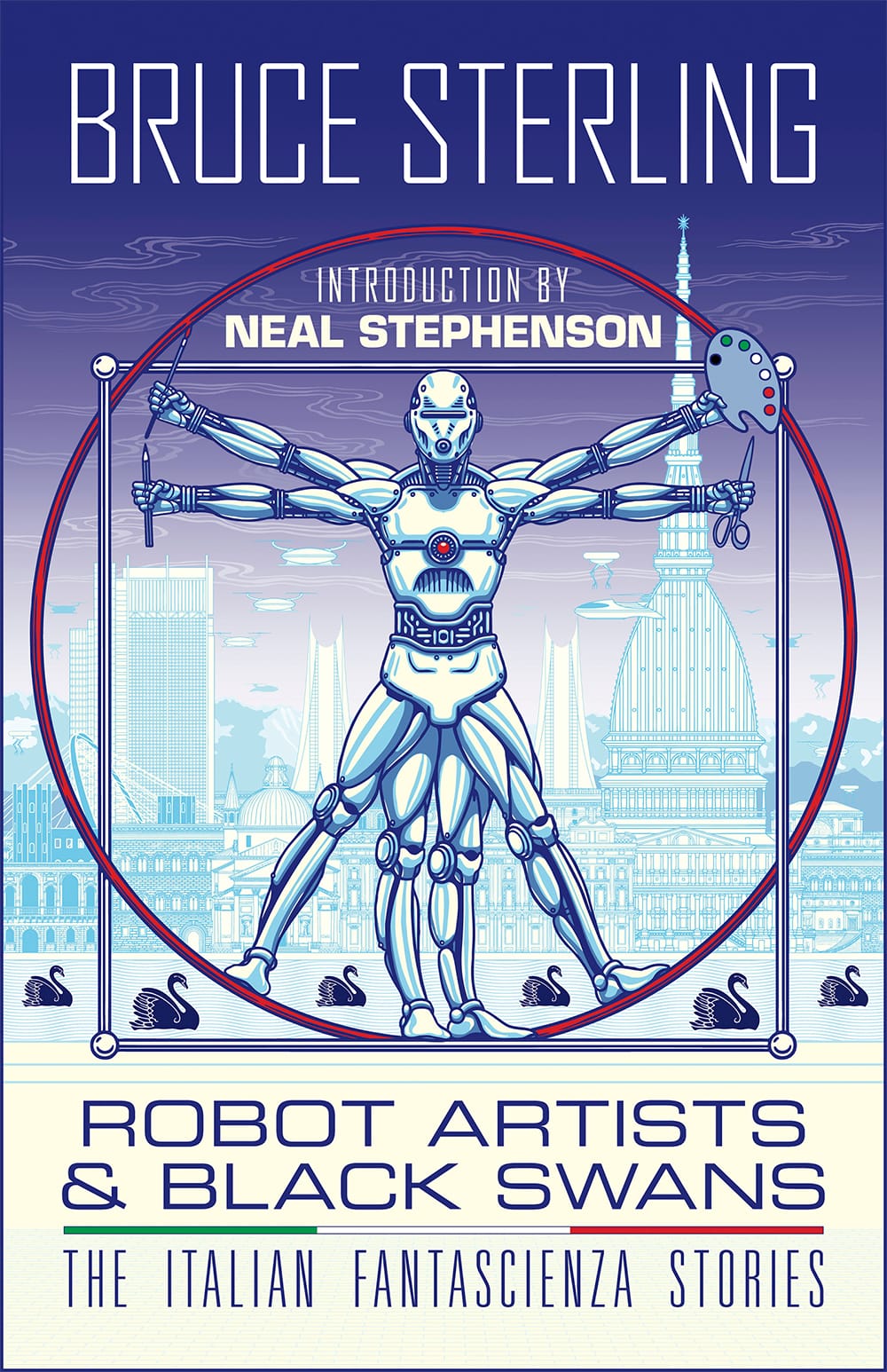

PGR: You’ve reminded me of something, and you’ve actually made it click for me in a way that it didn’t when I first read it. I was reviewing your collection of Italian stories, and the first story in the collection is very short, I think it’s like two and a half pages.

BS: “Kill the Moon”. It’s about a lunar luxury voyage.

PGR: Exactly. And I didn’t get what you were saying with it. I could see it was important to the collection, because you don’t lead a collection with an unimportant story, right? I could see it was meant to be the key to something, and I couldn’t quite get it. And I think you’ve started to open that up for me. Can you open it up a little further? I’m curious to know a bit more about how that story came together.

BS: I’ve written a lot of fiction here in Italy. And I’ve tended since arriving here to write fantascienza, rather than write as an American writing about science fiction in Italy. Fantascienza is a genre in the Italian publishing market, which is somewhat like science fiction, but not entirely. I mean, it has different cultural characteristics, and it’s also much younger; it didn’t really appear until 1957.

I know a lot of fantascienza practitioners, and I’m aware of their difficulties. So when I write fantascienza, I’m writing it for the Italian market, and I don’t write it in Italian. I mean, I can read Italian, but I would never be a great Italian writer. I do have an in-house translator, which is helpful, but nevertheless, when I’m writing a work like “Kill the Moon”, which was commissioned by Wired Italia, I was actually making a parallel between American and Italian lunar activities, right? I mean, it’s a space opera, it’s a sci-fi space story all about a rich guy going to the moon, where everything has been Italianized and everything has been luxuriated… and also the guy’s aim in doing this is a different thing, because he doesn’t consider himself an explorer. He’s more, you know, a Berlusconi figure—he’s a show off, he’s just doing it for the bravura, for the sake of the applause and for the glory of it, right? If you’re reading this from an Italian perspective, as a typical Italian Wired reader, you can see that it’s actually a comedy of cultural comparisons.

A lot of my earlier work was like that: I’m just going to take a standard kind of American sci-fi thing and costume-play it in Italian drag. But then as I grew more interested or more accustomed to Italian society, I started doing other stuff, which is more like writing what an Italian would actually write. You know, I kind of know where their bodies are buried. And the Italian difficulty with fantascienza is very sad. It’s kind of a cultural tragedy, in that there was a long tradition of very accomplished Italian fantasy writing, and then there was twenty years of fascist repression where all that stuff was just basically hit on the head and buried in a ditch. And then when they got out of that historically tragic situation, in the meantime, somebody had invented science fiction on another continent. It had like a twenty-year head start, and they discovered just this torrent of fantastic writing from the US and Britain that no one in Italy had ever seen, and they were just flummoxed by it. They really didn’t know what to make of it, they were put very much on the back foot—and no matter how hard they tried to write science fiction, it just never seemed to rack up to the professionalization of these fantasy factories from the Anglophone market, right? You know, British sf writers have a problem with the American market, but imagine an Italian trying to approach the Anglophone market; it’s like a guy in a dinghy confronting an ocean liner.

So I’m a very rare example of a guy who’s aware of this, and coming over not to write American science fiction, but actually writing fantascienza, right? I mean, it’s all about fantascienza’s topics, about being Italian. There’s scarcely any Americans in these stories; all the characters are Italian, the settings are all Italian, and the problems are Italian. The actual cultural issues that the stories are addressing are Italian. Now, I’m not actually Italian! But that actually adds to the exotic allure of these stories from an Italian perspective. They have the weirdness that a spaghetti western has for a Texan—you know, you’re watching an Italian spaghetti western about the Old West, it’s like, okay, they’re wearing jeans or carrying six guns, but their behavior is just, like, peculiar.

I never write, or rarely do I write, about contemporary Italian society. But I write a lot about Italian society 200 years from now, or 200 years in the past. There, I actually get a lot of of science fictional frisson. Because I’m rather well briefed about that; I mean, as a futurist, I’m super interested in trends. So if I don’t try to pass off myself as an Italian, but I write to Italians about the Italian remote future or the Italian remote past, it actually hits them. And I’m accepted—I mean, this is my Urania Award here, which is like the Italian Hugo Award, basically. So I would not say that I’m a major Italian fantascienza writer, but I do know the major Italian fantascienza writers. I’m a mid list Italian fantascienza writer, because I don’t work very hard.

I don’t think I’ll ever have an Italian best-selling novel. You know, I have books in Italian and published in Italy, they’re not published in English or in the USA, but my position here is kind of equivocal, and also I just don’t have the Italian popular touch—you know, I’m not a guy. I mean, if you’re, if you’re Italian, Joe Lansdale’s a guy—he’s basically like Philip K. Dick and H. P. Lovecraft for Italian fantascienza. Meanwhile, Bruce Sterling is like this weird, disturbing character... but on the other hand, I feel like my weird disturbance actually has an effect. I don’t write a lot of manifestos for the Italian fantascienza market, but it’s so small and I know people there so so intimately that I’m actually more of a consequential figure within those circles than you might think.

PGR: My tenure is not as long yet, but I’ve lived in Sweden for the last four years…

BS: Right. Yeah, that same thing. You have an outsider’s eye for that world.

PGR: And I find here when I speak to Swedes, there are some things that I don’t understand, that just I can’t get a grip on at all, that are just immensely obtuse. But there are other things that were obvious to me instantly on arriving, and when I mention them to Swedes they’re just not aware of at all… there’s that slippage, right? The question of what is tacit and what isn’t.

BS: In futurist terms, it’s the black swan and the pink flamingo, right? I mean, the black swan is something you just can’t see because you can’t imagine such a thing even being possible, whereas the pink flamingo is just like this hideous vulgar thing right in the middle of the lawn that all the locals ignore because they’re completely used to it. They just don’t see it at all.

PGR: Right—it’s blindingly obvious to you, and you stumble across it, and by stumbling across it you uncover something which is totally understood to everyone locally, but never discussed, right? We’re into the sort of Hemingway’s iceberg stuff—there’s a whole mass that you haven’t seen.

BS: That thing of Hemingway’s is of a lot of interest to me because, well, he said it. An American writer who’s wandering all over Europe, you know, trying to get under the skin of society. I mean, he does write a lot about Americans, but also he makes a sincere effort to understand the internal life of a Spanish bullfighter. And he’s also interested in kind of universal experiences, like what it’s like to be shelled in a trench. You find Hemingway of more interest after you’ve wandered about a bit.

PGR: Hemingway has kind of had a bad rap for a long time.

BS: He was an evil person in a lot of ways. I mean, I wouldn’t call him a person you would want to admire or imitate! I’m just interested in his historical experience, and his way of dealing with this. And I appreciate it that he’s not like, you know, passing up the pink flamingo aspects of European society—like, oh, look at these funny people, how stupid to get killed by a bull! I mean, he recognizes that it’s a meaningful choice, right?

Washington Irving is another author I’ve learned a lot about since coming to Europe. He was the (US) ambassador to Spain for a while, and also spent quite a lot of time overseas in Britain. He was a disciple of Sir Walter Scott, who found this teenager American guy and basically got him a publishing job; Walter Scott was extremely kind to Washington Irving. But Irving’s a guy who kept a lot of journals and had been a journalist, worked for newspapers and so forth. And he’s extremely observant about European society from an American perspective—I mean, he really notices the small, baroque-y knife style things, the shoes, the ways things are put together, figures of speech.

And he’s a big archivist. He’s always in the libraries looking for the historical roots of phenomena. You can go to a place like Granada, and the Spanish have built statues to him: “he came here when we were in terrible shape and our town was in ruins and he said that we were beautiful and the world would admire us if we just found our courage.” It’s like, he actually gave them a big pep talk as an American political advocate within Spanish society. He was very, very effective, and they were grateful.

You know, he didn’t scold them and tell them “stop being so weird, be more like us.” On the contrary, he actually kind of understood their distress. They’d been occupied by the French empire; Napoleon had come in and just wrecked the peninsula from top to bottom, just a horrible people’s war. And he knew how horrible that was. I mean, Goya-esque, right? Horrors of war, you know, the Goya paintings; it was that bad. And here’s this guy who’s supposedly a fantasy writer—he’s writing about the headless horseman, you know, funny ghost stories. And he’s aware of this utter European mayhem, and yet he somehow internalized it and can even like offer them a way out.

There's more on Washington Irving and Walter Scott to come in the second half of this interview. And if a discussion of genre fiction writers of the early C19th isn't enticement enough—trust me, it's more relevant to worldbuilding than you might expect!—then perhaps you'll be tempted by:

- the literary fabrication of the Italian national identity;

- the difference in attitudes to utopianism in Italy and and the Anglophone world;

- the distinction between science fiction and design fiction;

- and a deep dive on "Robot in Roses", a Sterling story which might represent a way past the obstacles that prevent C21st writers trying to think about the C22nd

Part 2 will drop on 22nd January 2025. Please consider signing up to the site, and get new publications emailed direct to your inbox!

Comments ()