design designs designers: an interview with Cameron Tonkinwise (part 1)

In this first half of my interview with Cameron Tonkinwise, we discuss design as a practice that necessarily takes place in an already-designed context, and what that practice has in common with worldbuilding.

Welcome back to Worldbuilding Agency for the first half of my interview with Cameron Tonkinwise, an Australian design scholar and educator, one of the minds behind the notion of Transition Design, and perhaps the first person I’ve interviewed who can actually speak in semicolon’d lists!

After we share a little gallows humour around “AI”, interdisciplinarity and the portfolio career, Cameron recounts his rather unusual journey from post-structural philosophy to design theory via Heidegger, before unpacking a whole cabinet full of chewy concepts for us.

We discuss the ways in which design can make us attending to one thing by making us attend away from another; we look at the ontological perspective on design, and the power afforded to designers; we explore Schatzkian time-spaces and the design of gerunds.

Ultimately, of course, we arrive at the matter of worldbuilding, and spend a bit of time discussing Vitiden, a vision of a decarbonised future Sweden. Let’s get on our way, shall we?

Cameron Tonkinwise: I’m a bit sad that you’re not going to take the recording and feed it into some AI synthesizer and then start just fabricating versions of me saying ridiculous things all over the internet. That’s what I was hoping you were going to do.

Paul Graham Raven: Well, I’d be lying if I said I hadn’t thought about it! If only because I know it would be a more interesting AI than one made out of me... to be confronted with the fundamentally repetitious nature of one’s own thought could be quite intimidating, I think.

CT: You remember Max Headroom? Where’s that version of a chatbot? I don’t see enough of that; I want to get a man in a rubber suit looking like a glitch, highlighting the fakeness rather than trying to hide it…

PGR: There’s a riff in one of the early William Gibson novels from the first trilogy, a character remarks that in a world where elective surgery is ubiquitous and affordable, the premium on beauty disappears. Looking distinctive becomes the thing instead; ugliness almost gains a premium of its own. If middle-of-the-bell-curve mediocrity can be faked, then all of a sudden being either strangely interesting on the one side, or lumpy and difficult on the other side... well, let's just say I’m holding a certain amount of hope for this.

CT: Your retirement fund is based on that aesthetic finally coming through, is that true?

PGR: Well yeah, no comment. You’ll have to speak to my accountant about that!

So—I usually start by saying, what does it say on your business card if indeed you have one? What do you do? What’s the elevator pitch?

CT: I have the enormous privilege of being an academic in an era in which that’s becoming a dying art. I am specifically associated with a minor field called Design Studies—so, I’m not a trained designer, but I teach designers how to think about their designs. Which, again, is a diminishing aspect of design education, because mostly they’re just taught how to design. And that’s why the world is going to pot: because nobody’s teaching them how to think about the consequences of what they’re doing, or how to take responsibility for their consequences, unless it’s a really comprehensive education and has some Design Studies in it.

My origins were a sort of failed philosophy—post-structural philosophy, in the great old days of the late 80s, early 90s. And then I kind of stepped backwards into design through a design theorist called Tony Fry. I did my PhD with him. I now spend most of my time teaching service design and researching transition design.

Uh, it’s a very long business card, sorry.

PGR: Well, this is why academics don’t have business cards, right?

CT: I think the business card is kind of a dying thing, partly because of the phenomenon of portfolio careers or whatever we’re supposed to call them.

PGR: So I’ve been accepted as a kind of... Malmö has an incubator for creative businesses, which sounds a bit more glamorous than it is. But I’ve been inducted into that this year, and we were up there having the introductory days yesterday. And I’m the oldest, whitest, straightest guy in the room by a long jolt, among all these brilliant kids. And no one’s like “oh, I’m a painter”; no one’s like “oh, I’m a musician”. No—they’re all musicians who do soundscapes around their paintings and also sometimes collaborate with jugglers, you know? Everyone is... and I think it’s been the case in academia for a while, but even saying “interdisciplinary” is like, oh, c’mon, who isn’t now? The borders have kind of gone.

Anyway: tell me about that—about that falling-into-design at the PhD stage. What sort of philosophy were you doing, and how did you fall out or sideways from it?

CT: It was the era of post-structuralism, in which people were paying attention to the material form of philosophy, all the way down to its typography, its book design. Some people were starting to notice multimedia, hypertext, and beginning to see that correlation, and then all the way up to the political institutions of philosophy, the bodies out of which philosophy was coming... it was like third-wave feminism, you know, a lot of focus on psychoanalysis, on the non-Marxist material side philosophy.

So I was in that. I was part of small stupid experimental groups trying to come up with alternative spaces for knowledge production. It was that great era when the noun ‘knowledge’ was in the plural, and you were constantly speaking about the knowledges of this, or the Foucauldian type of that. However, it was also the beginning of the end for that stuff; the reaction was still growing, and some figures were starting to die.

I was also not particularly rigorous at philosophy, and I kind of got kicked out of the philosophy school once some of the key post-structuralists left. I was left with more Marxist, Eastern European philosophers, and one particular philosopher said to me “look, you’ve given me three essays; I’m not really sure this is philosophy; I don’t know what you’re doing.” I walked out of the room and walked into a friend who said “there’s some really interesting people in—oddly enough—fine arts, and they’re talking about the philosophers you’re interested in, Martin Heidegger in particular. There’s this guy in fine arts who’s teaching Heidegger, but he’s a design theorist.”

So, the material side of philosophy at the time became a kind of switch point. I was looking for experimentation in material form and, without knowing it, I was talking about design: the design of communication, the design of institutions and organizations, the design of discourse, the apparatus and the set-up.

When I met Tony Fry, the design theorist, he came from a more Marxist background, but he was interested in Heidegger, and he was particularly an ecological politics kind of person. And he said, “what you’re looking for is a way of making ideas have agency, and design is that.” That’s how we define design: design gives ideas agency. They don’t have agency until they’re in a written form, in a designed form, in a media that’s actually going to disseminate them, etc.

So I did my PhD with him, which was on Heidegger. But Tony was also in the process of leaving the university; way back in 1991, he recognized that the university was inadequate to the challenge of sustainability—that it just wasn’t possible for it to actually have, what he calls, an imperative driving it. He was in the middle of setting up his own think tank, an independent research education institution called the EcoDesign Foundation. He still had the capacity to supervise, but he did a deal with me and said “I’m only going to supervise you if you come and work for this organization.” Throughout the 90s up until 2000, I did my PhD with him, but was also working at the EcoDesign Foundation, teaching sustainable design and thinking about sustainability. The whole point of that organization was to push sustainability discourse beyond cleaner production, eco-efficiency, beyond just making things less bad; it was about what later came to be called systems change, dematerialization, degrowth.

We have a mutual colleague [Clive Dilnot] who described Fry’s as the Old Testament version of sustainability: fire and brimstone, right? It’s going to smite you down! The rhetoric we had in the late 90s was that we are at war against unsustainability. It was quite seriously about a sort of extraordinarily forceful solidarity; and it was necessary to hold principles without any pragmatism when it comes to questions of sustainability.

That was my education. When Fry left that organization in 2001, I inherited EcoDesign Foundation for a couple of years; but there was a conservative government in power and I couldn’t make a go of it. In the meantime, I started developing design studies curricula for a local university, and then sort of got hired to start teaching it. Since then, I’ve stayed in the university, and I suffer a phone call from Tony Fry every couple of years asking me “why haven’t you left the university yet?” He’s done that for thirty years now.

PGR: Well, it’s good to know he’s still plugging away! Those old warriors are a necessity, I think.

“A way to give ideas agency.” That’s not a definition of design I’ve heard before—it’s incredibly concise! But, at the same time, it’s one of those doorway definitions: it sounds absurdly simple at first, but there’s a lot going on behind there. What does it mean to you? Take me through that doorway; what does it mean to give ideas agency?

CT: Firstly, at the most abstract but also the most simple, it’s that an idea has to be written to exist. I only know what I think if I write it down. Secondly, the idea will only begin to have agency if it is communicated, giving form to ideas. That form may be written text, but obviously it can also be multimodal.

Then you need to start thinking about who your audience is, and how you make this idea land. So in that sense, rhetoric is design—that was a point made by Dick Buchanan, albeit from a totally different perspective. He had this kind of Dewey-Aristotle-McKeon argument that design is the rhetoric of the technological arts, the rhetoric of the technological era. At that abstract level, design is part of argumentation, making choices about what and how you communicate: everything from phrasing to typography to paragraph breaks to word-image relations to the nature of the screen or paper, etc.

But the other, more substantive argument is something more like affordance theory, which is to say that if you want an idea to actually manifest in the world, you’re going to have to make things that help people do it. This is a kind of social practice theory argument, which is not at all Tony [Fry]’s language, but he was thinking in a similar way: ideas have agency when they become things in the world that allow people to see them and act on them and make them habitual.

Then you end up with the two sides of Bruno Latour. On the one hand, technology is society made durable: the moment society makes a decision that you can only drive 60kmh down a road, the only way to enforce that is to design the street in a particular way, or design street signs, or speed cameras for policemen; you give ideas agency by turning them into things in the world.

But those things in the world aren’t merely the presence of the idea; they’re obviously the attractor of the idea. They make the idea desirable; they make the idea necessary as a constraint; they make the idea convenient; they make other ideas, which are the opposite of that idea, more difficult. It’s a kind of energy gradient argument: if I want people to think this, I make the other thing more difficult to think or imagine or do, and so on. So, design gives agency by first giving ideas presence in the world, and then giving those presences a certain force because of affordances, because of the power of design.

At that point, you end up in an enormous conceptual difficulty, where is it’s either such a weak force that no one really pays much attention—“oh, well, yes, if it’s more attractive, people will use it more, but forget about it”—or they’re suddenly accusing you of some sort of materialist-behaviorist determinism.

The other side of Latour is, as you know, his almost material-practice version of religion; you don’t actually have a religion unless you have a ritual, unless you have a church or a temple to practice your religion in. So there’s a sort of design: you need to build the temple so that the god can come and reside in it; you have to give material presence to these things. And in that way, these ideas are also given agency because they have a materiality.

The reason why design gives ideas agency is because nothing exists until it’s being materialized, which is a design act. It’s a very anti-mentalist, anti-cognitivist kind of philosophy, whilst still being incredibly creative, because that’s the other side of design. Even though it’s material, and pragmatic, and affording use, it is nonetheless the creative act of making new things to hold new ideas, to create new habits, and new practices. It’s a process of change, never a sense that things are static.

PGR: When it comes to agency, when we talk about it in the abstract, I think it often gets conflated with freedom—and that’s kind of not necessarily the case. I’m thinking here of one of the definitions of design I remember best—one which I swear to God I remember Anab Jain from Superflux telling me, and which I’ve credited to her various times in public. Recently she said “thank you, but I really don’t remember ever saying that”, so I have no idea who it actually was... but I’m sure it was her!

Anyway, it’s something to the effect that design is about getting to choose what choices someone else has: the sense that, yes, you are affording the potential to do certain things, but at the same time you are unaffording other options. There is a closing down at the same time as an opening up.

CT: Yeah, absolutely crucial. I’d respond in two ways.

Michael Polanyi and Don Ihde have a related argument, from different perspectives, about the way technologies enable you to ‘attend towards’ something by ‘attending away from’ something else. I quite like this ‘tending’ or ‘attending’ language; it gives you focus, but it can only give you focus by blinkering out something else. It’s really important—and consequently very frustrating when you come across idiot designers saying things like “you’re all about politics, that’s not design! Design is not politics.” As you just said, design is making choices on behalf of other people. That is politics! It’s the most fundamental political act! You are putting things on the table and making them more likely, and you’re taking things off the table so that the table only has certain things on it.

Tony Fry is fond of saying that every act of creation is also an act of destruction. It works at many levels: if you’re going to make a chair, you’re going to kill a tree, so you should always be weighing the balance between what you’ve killed and what you create. But it goes in the other direction too, where you are creating certain habits and practices by displacing others. If I’m going to make something that’s going to allow people to look at the internet on their phone, I’m going to take them away from an experience of leaves shimmering in the wind while they walk down the street.

It’s not a hard and fast thing, more like an orienting, which is why the language of ‘attending away from’ is nice. You can train yourself to both look at your phone and notice the birdsong; it’s not like the designed thing forces you—though some designs can. Designers rarely recognise that they are in the elimination business as well as the creation business, in terms of the materials they consume but also the habits they’re creating.

PGR: I guess it connects also to the idea of the attention economy. One of my good friends and colleagues, Jay Springett, talks a lot about the sovereignty of attention—the sense that yes, we do live in a world where a lot of things are very effective at seducing our attention away from us, and that we should do our best to master our attention in response.

But back to the Tony Fry idea: OK, design is a way to give ideas agency, but there is also a sense where that very rigid way of thinking about design that you were just talking about is, whether intentionally or not, also an invitation for a person to surrender. Like, “my phone is just too attractive, what can I do? It’s the 21st century, I have capitulated to my designed environment”, right?

CT: You mentioned sovereignty. If design is about giving ideas agency, or about making choices for other people and limiting their choices, that then allows the people using a designed product to abscond responsibility and say “well, someone’s made a choice for me and there’s nothing I can do, I just have to go along with it.”

This relates to a really important point about Tony Fry’s philosophy—the Heideggerian stuff that’s called ontological design. The summary version of this argument is the mantra: designs design. As in, it’s not merely that you’ve designed a phone, you’ve also designed a phone that designs a person to behave in a particular way. So: designs design.

There’s a dangerous version of this, where it sounds like designers are these all-powerful people who are making ideas real, ideas that don’t exist until they’re designed, and then designers can make choices for people and so direct responsibility and things like that. That is an exaggerated version of the power of design—but on the other hand, I am troubled by designers who are quick to resist that framing. Any designer who says designers never have any power is somebody who, in my mind, never wants to take responsibility for what they design.

However, the frame of ‘designs design’ should always be understood also the other way, which is more like a Gadamer hermeneutic circle argument: you are designing within a world that has designed you. Whenever you get a design job, you think “oh, here are the things that are designable within this brief: I can change this, I can’t change that. These things are constraints; those things are variables. I’m going to focus on the variables, I’m going to solve the problem.” But the problem was designed by the world! It happens in the language of the brief, or even at the level of the logics that are framing ‘the contemporary.’ For example, the sense that you can’t possibly make things more inconvenient suggests that convenience is ontological for this design situation. You can’t possibly make things more uncomfortable; you can’t possibly make things slower! The only thing that’s designable is that which increases speed, that which increases efficiency; that’s what you should be designing!

As a designer, you are always being designed by the ontology—by the system, by the dynamics, the ideology, the power frameworks. You don’t have complete agency—or rather, it is version of that classic Marxist quip: humans can make history, just never in conditions of their own choosing. Parametric determinism! Your job as a designer is to try to work out what is currently within the material as dialectically designable. The job of the designer is to always try and redirect what there is to design.

Any designer worth their power is the designer who is always trying to understand how they’re being designed, and pushing against that to create new agency, rather than passively receiving the agency that the prevailing design setup is giving them. A designer has power to design a widget on a Facebook page that affects a billion people; that’s their power. But they also have the capacity to design so that people are aware of their impending mortality or cultural difference. They might get hit for that; their product manager is going to say “you can’t do that”, but they can fight for it. It’s straight-up politics at that point.

This is related to the way futurists talk about how the past is pushing society or an organisation in a particular direction, and how there will be certain things in the future that are pulling people. Your job as a futurist and as a designer is to try to change the forces behind you so that you’re looking in another direction, rather than the one that’s just the most likely result of this impetus pushing you there.

My job as a Design Studies scholar is to try to teach designers to see the way they’re being designed, so that when they design, they can ‘meta-design’ the design situations they encounter. But it’s going to be a struggle, and you might lose your job because you told your product manager that they’re an idiot because they’re just trying to juice their daily-active-use numbers, and things like that. The point is that designers always have some power, and they’re making choices, but within a particular ‘setup.’ Part of the mission of something like speculative design at its best is to try open other things to being designable.

This makes me think of another way to articulate this. People didn’t used to think services were designable! Services could be engineered, but you couldn’t design them. But now, as a result of some meta-designing, or ontological shifts, services are designable. People are starting to say, well, you know, maybe my career is designable! This was the whole stupidity of design thinking, which suddenly tried to declare all these different things were designable, though they weren’t. Nonetheless, it’s interesting historically to say “oh, people before didn’t think you could design that, but all of a sudden there are people who are designing it.”

So designers should go around trying to design things, and if they want to make degrowth lifestyles, they should be designing that. But it requires an act of meta-design; you can’t just simply design a widget to make it attractive to de-grow, quite apart from that being nonsensical!

PGR: What you’re saying there is that it’s not simply a matter of designing a thing, it’s a matter of designing the world in which that thing exists... the world that that thing implies. That’s kind of what I’m about, in many ways, as I think you know!

So this might be a good moment to ask one of the other cliché questions of this series: if I say the word “worldbuilding” to you, what do you recognise that word as meaning? Do you see it as having a connection to your own work? And if so, what is that connection?

CT: I love worldbuilding as an idea, as a way of characterising the power of fiction. I love it because Heidegger had this nice characterisation, and it’s kind of wrong, but it’s an interesting thing to think with: “Stones are worldless, animals are poor in world, and humans are world-makers.” He characterised the project of the work of art as the creation of a world. Charles Spinosa and Matt Hancock [and Haridimos Tsoukas] have just written a book called Leadership as Masterpiece Creation, and they basically characterise organisations as micro-worlds. The point of an entrepreneur, they argue, is to create a world; people enter that world and it has its own rules, exactly like a piece of fiction; if you haven’t built your culture that strongly, you haven’t shown what Spinosa et al call moral courage. They also say that Jeff Bezos is a perfect example, and I find it difficult to use the phrase moral courage and Jeff Bezos in the one sentence, but they do it quite plausibly, I think. It just requires a different sense of moral!

I totally agree with your paraphrase: the job of a designer is never to design a thing, it’s to design a practice. And practices are time-spaces, to use Theodore Schatzki’s term: time-spaces that have their own rules, like the kitchen, the workshop, the bus for a commute. You know, you’re not just designing a bus, you’re designing commuting. It’s amazing how often places like IDEO are so close to getting it right, and then they get it so wrong. They were the ones who wandered around saying, “the job of a designer is to come up with words ending in -ing”, verbal nouns. Designers should be trying to design commuting, or dinnering or, you know, swiping; that’s what you’re designing. And those are worlds—they’re time-spaces that have equipment and habits and meanings, and you know what you’re doing in them. We’re all hopping between different designed worlds all the time: the office and the kitchen and the commute and the garden.

I also love worldbuilding because it tells designers that their job is not the creation of just one thing, like an artefact: it’s always having to do many things in order to try to—again, as Heidegger characterises it—hold open that world. You can never just design the object: you have to design the object and its installation and its packaging and shipping and its repair; and how people learn to use it more, how they make it habitual; and it needs to fit with all the other things already in that time-space, and if it doesn’t fit then you need to change them as well. And all this is never possible as a one-time, once-and-for-all act of design, like total design. It is like the Diderot effect: you design a smoking jacket, and then you need the new slippers that go with it, and then the new rug that goes with the slippers, and then the room refurbishment that fits with rug, etc. Only then do you have not just the artefact but the world of a smoking jacket.

For me, worldbuilding is Transition Designing. I say to designers, don’t be serial monogamists, where you wait for one problem to come through the door and solve that, then wait for another problem and solve that one, and so on. Instead, worldbuild: stick with the one problem and build all over time all the things that are going to slowly accrete that world into existence. And defend its emergence—because that new world is going to be resisted, especially if it’s significantly changing existing worlds, competing with them…

Sorry, that was an over-enthusiastic answer! I meant to say that worldbuilding is a very good definition of design, as opposed to engineering or infrastructure or any of those words.

PGR: Please don’t apologize for the enthusiasm; not every designer I’ve spoken to about this shares it! Though I think in many cases that’s the inadequacy of my communication of what I mean by worldbuilding, as much as anything else—though certainly not in every case.

But, to build on that: obviously we’re both coming to the same questions from very different directions, but part of my interest in worldbuilding as a term is for its... I guess in a way I am trying to do something kind of designerly myself, in that by using worldbuilding as a term for what I think is fundamental to all forms of futuring, I’m looking for a way of getting us to a place in which all those different methodologies of futures work—from the really sort of trad futures-consultancy two-by-two-grid scenarios people, all the way to your kind of radical speculative designers, the narrative prototypers like myself—can recognise one another. I want to say “look, we’re all worldbuilding; we all do it really differently, sure, but that essential construction of a world is happening there.” It’s valued differently in those different methodologies, I totally understand that—but nonetheless, we are all in that business of imagining and exploring worlds.

You said something about design always being... in that chapter you sent me, you have a line in there, I noted it down: “life as an array of gerunds”. Life as verb nouns, as -ing words, right? That chimed with me because we’re at a point where it’s understood that there is this thing we call futuring, and that there are various ways of doing that. But to borrow that language from Tony Fry, perhaps: I see worldbuilding, in the sense that I use it, as an idea whose presence people will acknowledge, but it doesn’t feel to me like it has a lot of agency. What’s interesting to me about the idea of worldbuilding is that it means I can sit down with someone who does fairly trad scenarios work, and I can tell them there’s a translatability between what we’re doing—because if you make a world using the particular media and affordances that you do, I can then pick it up and I can build outwards to it, or I can take it and I can remix it.

I’m coming to this question of worlds from Mieke Bal’s model of narratology: you have text, story and world, and it’s like the reverse onion, in that every time you go further in, it’s bigger inside. But the crucial observation from that theory—which I don’t think Bal really investigated very much, because she wasn’t interested in general literature—is the sense that the world is not exhausted by the story, and the story is not exhausted by the text.

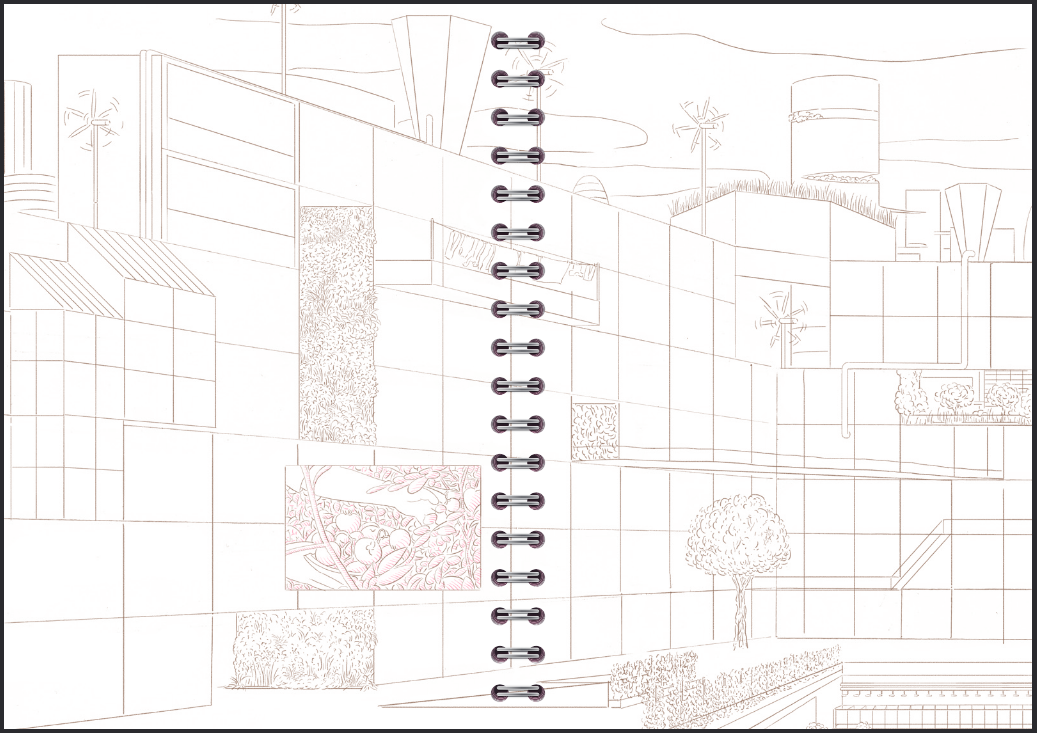

Actually, the best thing to do is to illustrate the idea, with a project from KTH in Stockholm, called Vitiden. So, the Swedish Energy Agency did a classic four-scenarios thing, you know, “here are four scenarios and ooh, look at this one in the top right corner; this one looks preferable to the others, doesn’t it?” A really classic, top-down, “if we just reduce, if we do this and we do that, blah blah, then everything will be fine” sort of scenario. But it’s very much not the day-in-the-life-of stuff; it’s more like the architectural maquette looking down. It basically says “if we just reduce our carbon emissions, everything will be great.” Well, okay—but what does that actually look like, on the ground?

What they did with Vitiden was to say “okay, we’re going to take that scenario at its word, and we’re going to ask ‘what does that look like?’ We’re going to design that; how can we bring that to life?”

[some fruitless moments are spent searching some extremely disordered bookshelves]

Well, I have a physical copy somewhere! Like a lot of prototypes, it’s so much more magical when it’s a thing in your hands, but you can get it as a PDF. I use it as an example in talks all the time, precisely because it’s so fantastically mundane. It’s a very, very Swedish example, but one of the pages, it’s just a menu from a pizza restaurant—in Sweden, every third block will have one of these little things, just a little corner fast-food joint. So this is the sort of menu that any Swede will have seen once a week for their entire lives.

And I’ll show it, particularly to audiences of Swedes, and I ask “do you all recognise this? Now, can you see the different world in here?” Because I have presented this to them as an artefact from the future. But I often have to point out to them that there is one pizza on that menu which is three times the price of the other ones; what is different about it? And then I watch the faces as it clicks for them: oh, right, it’s the pizza with the meat toppings! There is something about being made to work for that realization that really unlocks the whole thing.

Clearly, you can achieve that effect without theorising it through worldbuilding, because I don’t think the Vitiden research team thought about it that way at all. But this example is a way of saying that, once you can look at futures as worlds, a kind of transposability between media becomes possible. I can take that future you have made, and I can put it into another medium; I can add to it with different forms; I can build on it, I can put more characters in that world and see it from different perspectives. But also I can remix it, I can cover it from a different angle, I can show it in a different light.

It’s like you were saying earlier about designers who say “there is no politics in design.” It’s a way for me of saying to the people who say “no, no, futures is not really about politics, it is just about strategic decision making”, for me to say to them well, what the fuck else is politics, if not that? You don’t have to like it, mate, but we are all doing the same thing here!

The question is how exactly are we doing it, and to what ends…

That’s all for this month! Please pop back next month for the second half of my chat with Cameron, where we get stuck in to Transition Design itself—which, as he says, bears a fair bit of resemblance to worldbuilding in both theory and practice—as well as the pros and cons of “show, don’t tell”, how Superflux and Proust used similar techniques in very different media, the poverty of Futures Literacy, and the prefigurative imperative of designing new desires.

If you enjoyed this interview, please forward it to a friend who you think might also enjoy it!

If you really enjoyed this interview, perhaps you'd like to sign up to receive Worldbuilding Agency by email? It won't cost you anything, and you can unsubscribe with just a few clicks at any time...

Comments ()