week 29 / 2024

This week: ethnography-in-reverse as an analogy for narrative prototyping... and the infrastructurality of the scroll-wheel?

To all of those among you who asked me whether I would be taking a summer vacation this year, and who received a reply along the lines of "probably, but part of me would rather be working": please accept this as my admission that tempting the universe with statements like that is unwise in the extreme.

Ticked off

Here's what I've been up to this week:

- Meetings—so many meetings!—for PROJECT TEMPORAL. (Discussing project contributions with those who will be writing them; see One Big Thing below.)

- One meeting for PROJECT HOTPLATE. (A many-handed bid-writing thing, to be poked at over the summer.)

- Drafted a kick-off essay for This Very Website, which should be done and posted by the middle of next week.

- Celebrated the publication of a chapter which I consider to be my academic swan-song. (All publication is bittersweet, but this one particularly so.)

- Went for a beer with Duncan Geere. (Rhyming social engagements are the best social engagements!)

- Rearranged my kitchen around the rather nice microwave I've been gifted by a friend who's relocating to the countryside. (However, there is no user manual available for this model anywhere on the internet, or at least the internet reachable by search-engine; this meant my first attempt at defrosting was, perforce, cautious and experimental.)

- Dug out and dusted off my old Cambridge Audio CD player, which I bought maybe two decades ago, and cabled it into my network receiver so I can (gasp!) listen to music without turning on a computer. (Where "being an incorrigible pack-rat" meets "leaning into accusations of being a neoLuddite".)

- Finished reading The Book of Love by Kelly Link. (Over 600 pages of Not My Usual Sort Of Thing; it takes a very good writer to keep me interested in genres and/or styles that don't flick my main switches, but Kelly Link is a very, very good writer indeed.)

One Big Thing

The participants I'm working with in PROJECT TEMPORAL are mostly academics, and the ones that aren't are pretty much academic-adjacent. The aim of the intervention that I and my co-producer are working on is to use a fictional space to allow the participants to bring together and explore the various temporal issues and questions that they are engaged with as researchers, but in a manner that will make them accessible and engaging to non-specialists.

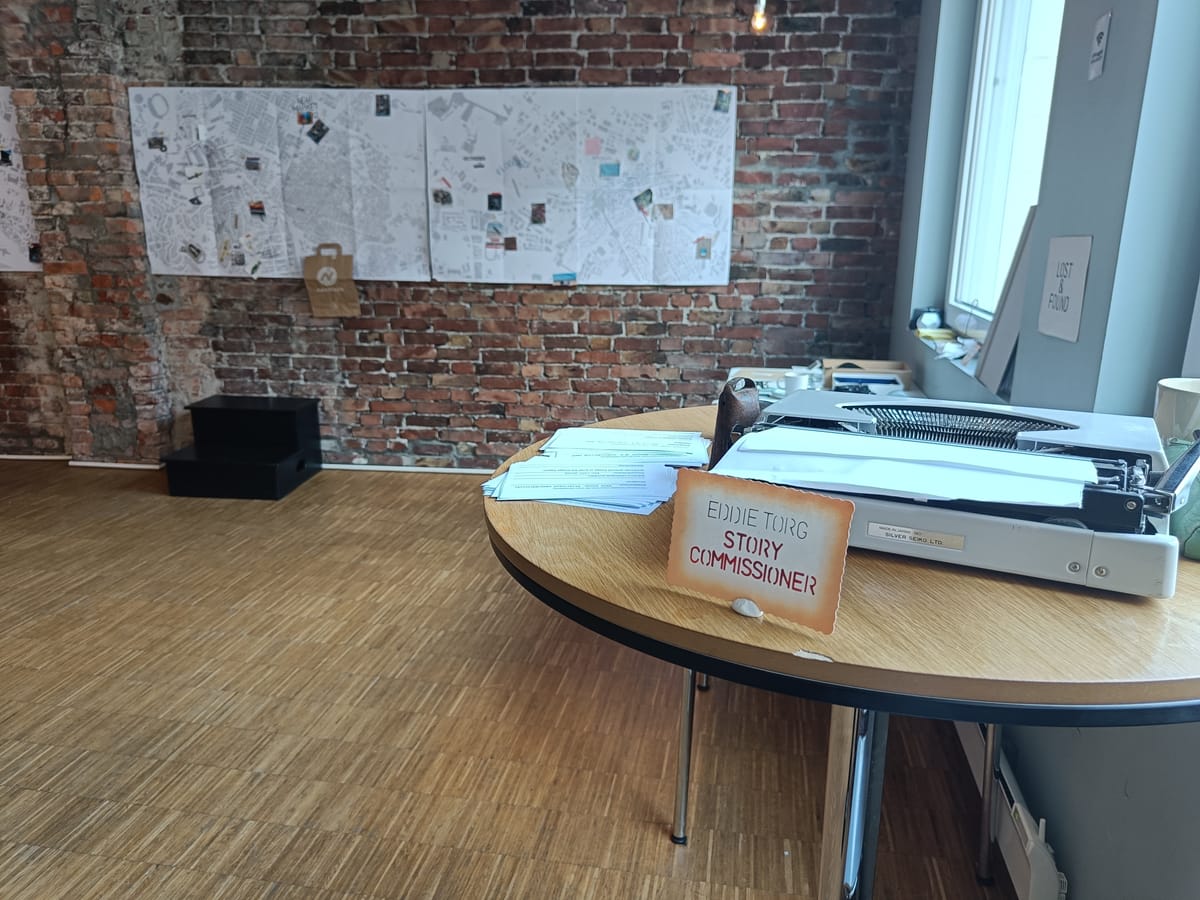

Those familiar with my work from the last five or six years will know that this is exactly what I think narrative prototyping is good for! But in this project, I am facilitating the expertise of others, in a field where I am not yet very knowledgeable myself; I am also operating on a pretty limited budget, both financially and (ironically enough) temporally. Which is to say: I cannot simply produce loads of the material myself! Rather, I find myself needing to play the role of magazine editor not only figuratively/theatrically, but also literally: working with writers to develop ideas into stories which they feel capable of writing (or at least drafting up to a point where I can hammer them into shape).

The challenge here is to get them to avoid the five-dollar theory-words that are an academic's stock-in-trade. In general, I have very little time for the argument that academics should write about their work in a way that can be understood by the lay public: academics need specialist language for the same reasons a mechanic needs specialist tools. Or, to put it another way, the abstractions of theory cannot be simplified without their being rendered banal in the process.

The work of narrative prototyping, however, is not the simplification of abstraction, but rather its (re)concretisation. To use an example I intend to expand upon in the months to come: it would be possible for me to write a brief summary of social practice theory that expressed the key points of that school of thought with regard to the challenging nature of sociotechnical change. But in the absence of examples—without cases that can be used to illustrate the real-world human-scale dynamics that the theory attempts to understand and explain—I might as well be explaining the emergence of capacitance as a function of potential difference applied across two electrodes separated by an electrolyte: you might well memorise the equations and the terminology, but if you didn't already have a grasp of the role of capacitance in electrical circuitry, that knowledge would be useless.

Fiction (and journalism, fictional or otherwise) can serve this purpose of concretisation. Instead of merely telling you that any one person's particular expression of a practice-as-entity is necessarily and inescapably shaped by the skills and knowledges they have acquired, by the devices and infrastructural affordances they have available to them, and by the meanings they attach to the performance of the practice in question, I can instead show you people (real or imagined) in the process of doing things, and finding their doings constrained by their circumstances.

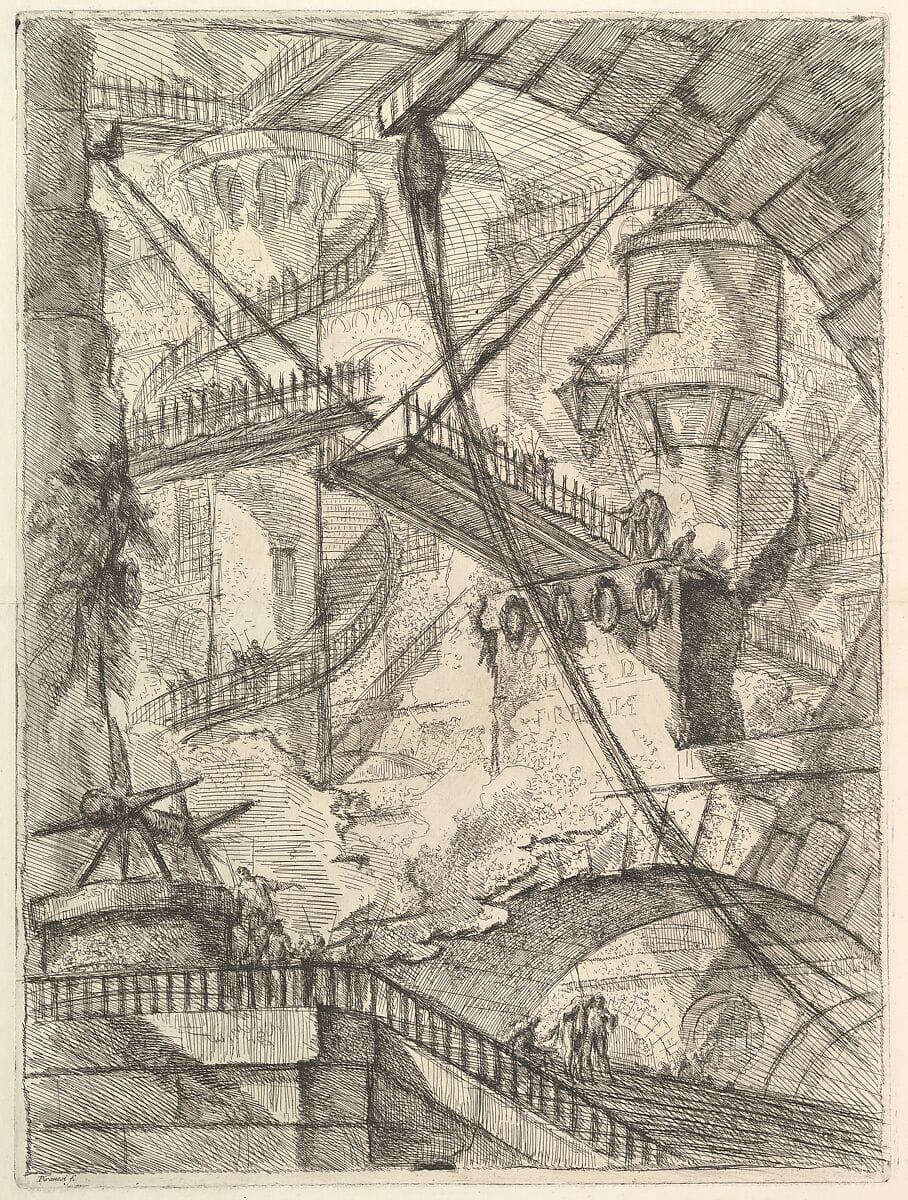

This process, it seems to me, is rather like ethnography in reverse—and that's exactly how I've been explaining it to the participants in PROJECT TEMPORAL. It's a (re)concretisation of theory: you've developed those abstract ideas through study of the real world, and now you're building an imitation of the real world with which to exemplify the theory.

However, the comparison to ethnography also brings to the fore some of the problematics of narrative prototyping—and the advantage of working with academics is that those problematics are broadly understood. It feels to me like a lot of the clashes in recent years over what we might charitably refer to as naive deployments of design fiction come from those deployments having taken place in environments where the ethnographic problematics are not understood—and that's one of the issues I'm hoping to address with my writings here at W.A.

More immediately, however, I think the "imaginary ethnography" comparison will continue to be fruitful for creative futuring work in academia, or along its margins. Because that movement between the abstract and the concrete and back again is, if you ask me, the heart of all futures work, in all its very different modes of expression, in all the possible contexts of its deployment.

(It is the movement of the shuttle across the warp and the weft of the worldbuilder's loom, if you'll forgive me a little poetic license on a Friday afternoon...)

One Small Thing

It's a cliche of STS and contemporary infrastructure studies to note that infrastructure is that which we only notice at the moment of its failure. (Shout-out to Susan Leigh Star, and many others.)

As such, there is an argument for the scroll-wheel as infrastructure: the one in the mouse on my main work desk at home has gone for a burton, as we Brits sometimes say, and good lord I hadn't realised just how much I use that damned thing, until suddenly being obliged to use the cursor keys on my keyboard instead.

(Said keyboard and mouse are actually a rather nice Lenovo outboard set, and were bought at the same time as the laptop to which they are attached, which is to say four and a half years ago, when I first arrived in Sweden. I dare say I've punished both of them pretty hard, but even so, it really feels like things should last longer before becoming e-waste.)

A Clipping

You can't spend long talking or thinking about futures prefigurative, preferential and experiential without running into Stuart Candy.

His blog sprang back into life last week with a long write-up of a recent project of his, titled Sing Wild Seeds:

... a project about having musicians and audiences pre-enact preferred futures together.

Conceptually, it springs from a question along these lines: how might music-making be combined with experiential futures towards developing our collective ability to imagine and shape desired change?

Institutionally, it’s a collaboration between the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) and Earth/Percent, both independent UK-based social change organisations, dedicated respectively to accelerating the “transition to a more equitable and just future”, and “unleash[ing] the power of music in service of the planet”.

Said project not only involved the one and only Brian Eno as co-facilitator, but apparently also took place in Eno's studio?! I guess that's how you know when your work has really started to take you to interesting places, literally as well as figuratively...

This has been the Worldbuilding Agency weeknotes for Week 29 of 2024. Thanks for reading! If you've enjoyed them, it's free to subscribe, but please consider supporting this research journal with a small monthly payment—you'll get access to the occasional bit of Exclusive Content ™️, and you'll be funding free subscriptions for those with fewer monetary resources, but first and foremost you'll get the warm glow that only ever comes from enabling fully independent and climate-focussed foresight research to continue.

(If you are already subscribed, please send to a friend who you think might also like it!)

Have a good weekend.

Comments ()